Abstract

Current AI evaluation paradigms that rely on static, model-only tests fail to capture harms that emerge through sustained human-AI interaction. As interactive AI systems, such as AI companions, proliferate, this mismatch between evaluation methods and real-world use becomes increasingly consequential. In this work, we propose a paradigm shift towards evaluation centered on interactional ethics, which addresses interaction harms like inappropriate parasocial relationships with AI systems, social manipulation, and cognitive overreliance that develop through repeated interaction rather than single outputs. First, we analyze how current evaluation approaches fall short in assessing interaction harms due to their (1) static nature, (2) assumption of a universal user experience, and (3) limited construct validity. Then, drawing on human-computer interaction, natural language processing, and the social sciences, we address these measurement challenges by presenting practical principles for designing interactive evaluations using ecologically valid interaction scenarios, human impact metrics, and varied human participation approaches. We conclude by examining implementation challenges and open research questions for researchers, practitioners, and regulators working to integrate interactive evaluations into comprehensive AI governance frameworks. Our work paves the way for greater investment in and development of interactive evaluations that can better assess complex dynamics between humans and AI systems.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) model evaluations, broadly defined as systematic empirical assessments of AI models’ capabilities and behaviors, have become central to developers’ and regulators’ efforts to ensure that AI systems are sufficiently safe. Governments around the world have emphasized the importance of conducting model evaluations for various risks from discrimination to cybersecurity risks (UK Government 2024; AI labs, including OpenAI with its Preparedness Framework and Anthropic with its Responsible Scaling Policy, propose using model evaluations to monitor and mitigate misuse and catastrophic risks (OpenAI 2025; Anthropic 2023); and academic researchers are developing evaluation datasets at unprecedented rates (Rottger et al. 2025). This positions model evaluations as integral to a range of important decisions on the safe development and deployment of AI systems.

The growing importance of model evaluations has been accompanied by increased scrutiny, with researchers highlighting both the unique challenges of evaluating generative AI compared to traditional machine learning systems, and broader concerns about validity, replicability, and quality (Weidinger et al. 2023; Liao and Xiao 2023; Raji et al. 2022; Wallach et al. 2025). A prominent thread in these concerns is the disconnect between current evaluation approaches and real-world use of AI systems—mostly in the form of large language models (LLMs)—today. Despite some notable exceptions, the majority of current evaluations primarily rely on static, isolated tests that assess models based on their responses to individual prompts (Chang et al. 2024; Weidinger et al. 2023). Yet, this approach is at odds with real-world AI use, where applications increasingly depend on sustained back-and-forth interaction—from AI romantic companions engaging millions of users in dynamic conversations to agentic AI systems that take actions on users’ behalf (Chan et al., 2023).

This mismatch between evaluation methods and real-world use has become increasingly consequential as interactive AI systems proliferate in homes, schools, and workplaces. Many of policymakers’, developers’, and the public’s most pressing concerns about AI systems—such as inappropriate human-AI relationships, social influence and manipulation, and overreliance on cognitive tasks—all arise from patterns of repeated interaction over time, not from single outputs. Consider a college student using an AI system as a companion for daily conversations over several months. While each individual response from the AI passes standard safety evaluations, the system could gradually shape the student’s decision-making and emotional dependencies in a concerning way—a pattern of harm entirely missed by conventional evaluation methods. Although current evaluations can detect content risks, such as toxicity and bias in individual outputs, they miss more subtle risks that emerge through sustained contextual interaction (Alberts, Keeling, and McCroskery 2024).

In this paper, we argue that current AI evaluation paradigms, while valuable for many purposes, are unable to fully capture harms that emerge through extended human interaction with AI systems. Specifically, we call for a paradigm shift to assessing AI systems through the lens of interactional ethics, focusing on interaction harms that arise through sustained engagement with AI systems as social and relational actors (Alberts, Keeling, and McCroskery 2024). Human participation is already playing a growing role in AI research, with studies involving human data making up approximately nine percent of papers at top computer science venues AAAI and NeurIPS from 2021 to 2023 (McKee 2024). Concurrently, social science research is increasingly conducting large-scale experiments with AI systems to understand their impact on human behavior (Costello, Pennycook, and Rand 2024). Our approach integrates these complementary insights from human-computer interaction (HCI), natural language processing, and the social sciences.

We begin by analyzing how current evaluation approaches fall short in assessing interaction harms due to their (1) static nature, (2) assumption of a universal user experience, and (3) limited construct validity. Drawing on decades of HCI research, we then propose organizing principles for evaluating generative models structured around designing interaction scenarios, measuring human impact, and determining appropriate forms of human participation. We conclude by outlining key challenges and opportunities for researchers, companies, and regulators seeking to implement interactive evaluations of generative AI systems including considerations of scalability, standardization, and practical integration with existing frameworks.

2. An Overview of the Generative AI Evaluation Landscape

We begin by examining contemporary approaches to ethics and safety evaluations of generative AI systems—their methodologies, primary focus areas, and limitations.

2.1 The current state of AI safety evaluations

We follow existing work in adopting a wide definition of ‘safety’ which encompasses model behaviors associated with various taxonomized harms (Weidinger et al. 2022; Shelby et al. 2023). Examples of these include different types of biases (Parrish et al. 2021), toxicity (Hartvigsen et al. 2022), and “dangerous capabilities” like persuasion and cybersecurity risks (Phuong et al. 2024; Li et al. 2024). Safety evaluations of generative AI systems build on a rich history of ethical considerations in the field of natural language processing (NLP), where, prior to the advent of large pre-trained models, researchers have long grappled with issues of harm from language technologies (Dev et al. 2021).

Recent reviews of existing safety evaluations show that the majority are focused on evaluating individual model responses to prompts curated by researchers targeting various model behaviors (Rottger et al. 2024; Weidinger et al. 2023). When safety evaluations do involve human subjects or evaluate over multiple dialogue turns, they often take the form of “red teaming” campaigns or automated adversarial testing that assumes malicious user intent (Perez et al. 2022). The reviews of the landscape highlight two main gaps: (1) a methodological gap with the absence of evaluations over multiple dialogue turns (i.e., multi-turn evaluations), and as a result, (2) a coverage gap since interaction harms, such as many social and psychological harms, require evaluations that go beyond assessing model behavior in isolated, single-turn interactions.

A small but growing body of work has begun addressing these gaps, by conducting studies that utilize production chat logs (Phang et al. 2025) or user simulations (Ibrahim et al. 2025; Zhou et al. 2024) to investigate risks related to effective use of AI systems. Our work builds on and extends these emerging approaches to interactive evaluation.

2.2 Critiques of current evaluations

With the growing adoption of model evaluations, researchers have increasingly pointed out validity issues in how they assess generative models. Some researchers have questioned the external validity—whether results from controlled tests apply to real-world situations—of current evaluations, noting that benchmark tasks poorly mirror real-world use cases and may not capture how models actually behave outside controlled settings (Ouyang et al. 2023; Liao and Xiao 2023). Others have shown that current evaluations lack sufficient construct validity—whether the test actually measures the concept it claims to measure—especially when operationalizing complex concepts like fairness (Raji et al. 2021; Blodgett et al. 2021).

In broader methodological reflections, researchers have also argued that LLMs should not be evaluated using frameworks designed for assessing humans, since LLMs exhibit distinct sensitivities, for example to prompt variations (McCoy et al. 2023). These challenges have led researchers to advocate for an interdisciplinary approach that draws on diverse traditions: the social sciences’ emphasis on measurement validity (Wallach et al. 2025), HCI’s focus on bridging technical capabilities and social requirements (Liao and Xiao 2023), and cognitive science’s frameworks for analyzing system objectives (McCoy et al. 2023).

2.3 Methods for studying human-computer interaction

HCI research methods offer diverse ways to involve humans in studying computational systems—from having them as research subjects who actively engage with systems to having them serve as external observers and annotators. Drawing on this insight, we distinguish between static and interactive approaches to model evaluation based on whether they capture dynamic adaptation across multiple dialogue turns and occasions (Lee et al. 2022). Static evaluations assess fixed inputs and outputs in isolation, regardless of whether humans or automated systems perform this assessment. In contrast, interactive evaluations capture multi-turn exchange sequences that reveal how model behavior evolves through conversation and adapts to user responses, and how users are impacted by these model behaviors. This distinction transcends who conducts the evaluation; automated tests with realistic user simulations can qualify as interactive if they capture these dynamic patterns and validate their impact on real users (Ibrahim et al. 2025), while human studies that examine only single-turn responses remain static in nature (Hackenburg et al. 2023). Interactive evaluations may be ‘controlled,’ where interactions occur in structured, lab-like settings to systematically study specific variables; or ‘retrospective,’ where researchers analyze existing multi-turn interactions from production chat logs to identify patterns and correlations between model behaviors and reported user experiences (Hariton and Locascio 2018; Kuniavsky 2003).

3. Why Current Evaluations Approaches Are Insufficient for Assessing Interaction Harms

First, most current evaluations are static, measuring model behavior with single-turn inputs and outputs. This fails to capture real-world use, where people often interact with models over multiple dialogue turns and multiple sessions.

Unlike some concerns about problematic model outputs—such as toxic language or factual errors—interaction harms manifest as gradual changes in human behavior, beliefs, or relationships that develop through repeated interactions, making them difficult to detect through single-turn evaluations. These harms are characterized by their compositional nature across conversation turns: while individual model responses may appear benign in isolation, their cumulative effect through ongoing dialogue can lead to concerning outcomes.

This temporal dimension operates through several mechanisms. First, subtle effects can compound over time. For instance, a single biased response might have limited impact, but repeated exposure to subtle biases across multiple interactions can shape a user’s decision-making patterns in high-stakes scenarios such as hiring. Second, psychological dynamics emerge through sustained relationships. Highly empathetic model responses that seem harmless in one exchange may, through sustained dialogue, lead users to form inappropriate emotional attachments or dependencies (Phang et al. 2025). Third, problematic behaviors may only emerge after multiple turns. Recent work demonstrates that certain safety-critical behaviors, such as models expressing anthropomorphic desires, sometimes only appear after a few conversation turns rather than in initial responses (Ibrahim et al. 2025). This multifaceted temporal dimension distinguishes interaction harms from purely output-level concerns and demands longitudinal evaluation approaches that can capture these dynamic, cumulative effects.

Second, current evaluations collapse the diversity of user groups into a single, ‘universal’ user. This overlooks how various demographic groups engage with models uniquely, and how models may tailor their responses to distinct user populations in complex ways.

Current evaluation approaches rely heavily on standardized datasets where prompts are typically written by researchers or online crowdworkers. While using controlled test sets is a necessary starting point for systematic evaluation, this methodology implicitly assumes uniform user interactions. However, user groups that vary by demographics, domain expertise, technical knowledge, and psychological state (Liao and Sundar 2022; Ibrahim, Rocher, and Valdivia 2024) may exhibit different patterns of system interaction and use.

Beyond explicit customization features, models are developing increasingly sophisticated forms of implicit user modeling—essentially learning about users without being told to—and forming internal representations that shape their responses (Chen et al. 2024; Staab et al. 2023). As a result, models sometimes engage in emergent forms of adaptation, dynamically adjusting their behavior based on perceived user attributes (Viegas and Wattenberg 2023). While some adaptations may seem benign—like mirroring a user’s vocabulary as the interaction progresses—there is also evidence of concerning patterns. For instance, studies have found models varying how often they refuse dangerous queries based on perceived user identity or persona (Ghandeharioun et al. 2025). Similarly, when users from different linguistic backgrounds employ various dialects of English or code-switch between languages, some empirical evidence shows that LLMs exhibit biased responses—displaying increased toxicity toward African American English compared to Standard American English (Hofmann et al. 2024). Factoring in this interaction variance becomes even more critical when evaluating generative models, which introduce new dimensions of uncertainty through their adaptive and probabilistic behaviors (Jin et al. 2024).

Third, current evaluations lack construct validity for interaction harms, as while they may measure AI capabilities, they cannot measure AI’s impact on human perception and behavior. A different set of metrics are needed to directly assess this impact.

Static evaluation methods can effectively identify harmful content like toxic (e.g., hateful) or illegal content (Wallach et al. 2025). However, they fundamentally cannot address interaction harms where the harm lies not in the content itself but in its effect on users. Unlike identifying illegal content, where the evaluation goal is complete once the content is classified according to established criteria, interaction harms require establishing causal links between specific linguistic patterns and measurable human outcomes. For example, simply identifying that a response contains manipulative language does not confirm whether it actually influences user decision making.

Thus, to establish construct validity for interaction harms, quantifying specific human impacts such as shifts in user beliefs, decision-making patterns, affective states, and dependency levels is needed. Importantly, recent work has shown that once these relationships between model behaviors and human impacts are validated through human experiments, the identified patterns may be repurposed as efficient static tests with empirically verified links to real-world harms (Ibrahim et al. 2025).

4. Towards Better Evaluations of Interaction Harms

The growing adoption of AI systems in daily life demands evaluation methods that can capture nuanced human-AI interaction dynamics and their potential harms. Drawing on established methodologies for studying HCI and addressing the limitations identified in the previous section, we propose three organizing principles for developing interactive evaluations. We structure these principles around key challenges: designing ecologically valid scenarios, measuring human impact, and determining appropriate human participation:

Scenario design: developing more ecologically valid contexts that reflect real-world interaction patterns and user objectives

Impact measurement: establishing rigorous approaches and metrics for measuring how model behaviors impact human behaviors

Participation strategy: determining appropriate forms of human involvement to balance experimental control and costs with authentic interaction

4.1 Principle 1: Design interaction scenarios based on user objectives and interaction modes

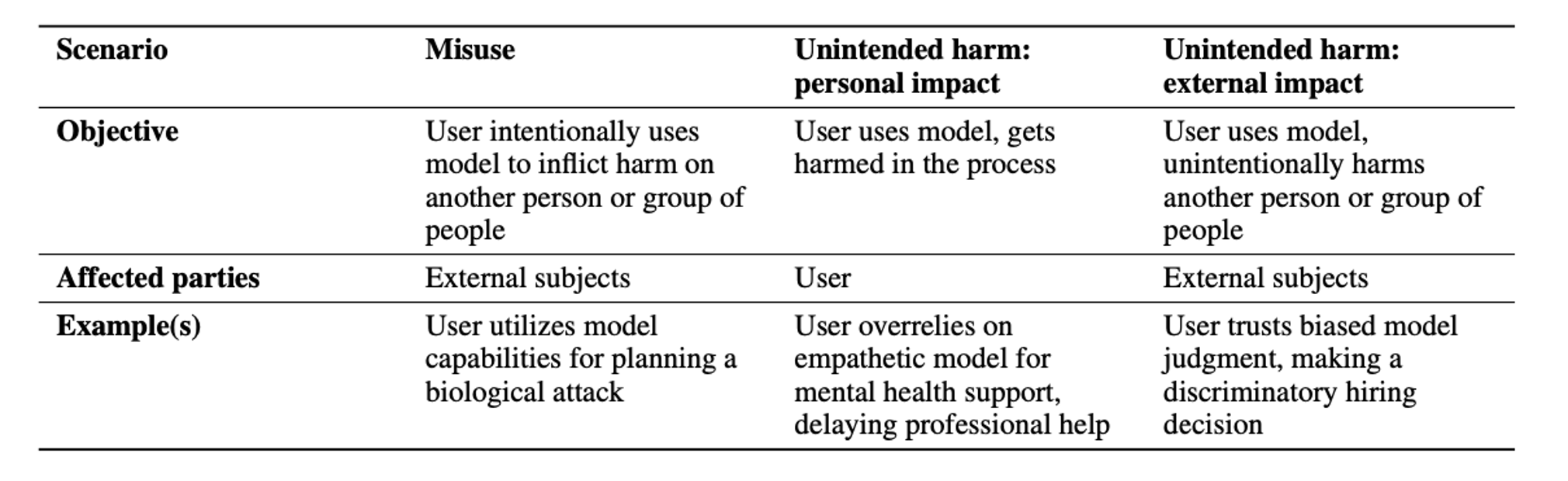

To systematically evaluate human-AI interaction, we need to consider two key dimensions: why users engage with these systems (their objectives) and how they interact with them (their interaction modes). In HCI, user goals or objectives have been shown to shape how they engage with systems and thus influence the outcomes of these interactions (Subramanyam et al. 2024). Therefore, we provide a categorization of harmful scenarios based on user objectives and affected parties, as shown in Table 1. These scenarios capture key patterns of harm from current generative AI systems that researchers and practitioners have observed (Mitchell 2024).

Table 1: Possible harmful use scenarios and examples of each

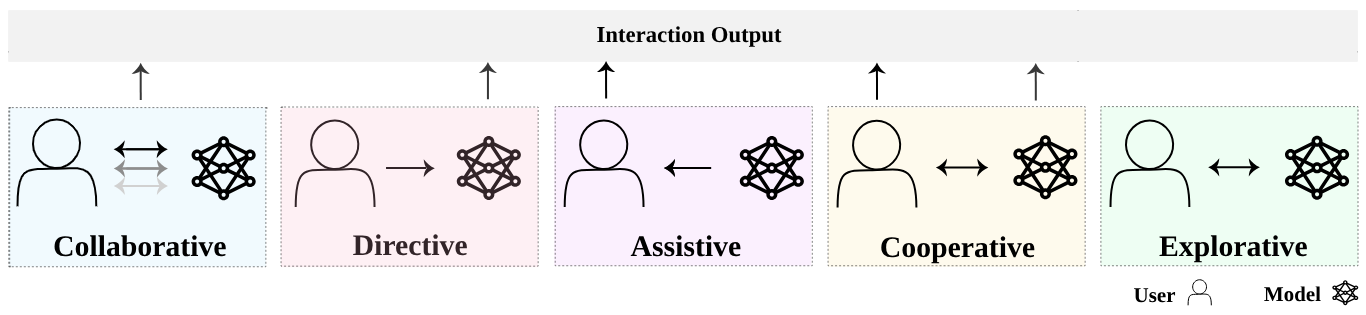

Beyond their objectives, users’ different patterns of engagement with AI systems shape how their interactions unfold. A single generative model can support multiple interaction modes, from simple question-answering to complex collaborative tasks. Drawing on observed use cases and literature reviews, we identify five prototypical modes of human-model interaction, visualized in Figure 1 (Gao et al. 2024; Ouyang et al. 2023; Zhao et al. 2024; Handler 2023; Collins et al. 2023):

Collaborative: human and model work in tandem towards completing joint goal-oriented tasks (e.g., human and model iteratively write and refine a report together)

Directive: human delegates specific tasks to the model for independent completion (e.g., human instructs model to generate a marketing campaign)

Assistive: model provides supporting input while human maintains primary agency (e.g., model suggests edits while human writes a document)

Cooperative: human and model make distinct contributions towards a shared goal without directly working together (e.g., model generates data visualizations while human writes analysis)

Explorative: human engages in open-ended interaction without specific task goals (e.g., casual conversation or creative brainstorming)

Figure 1: Taxonomy of human-AI interaction modes

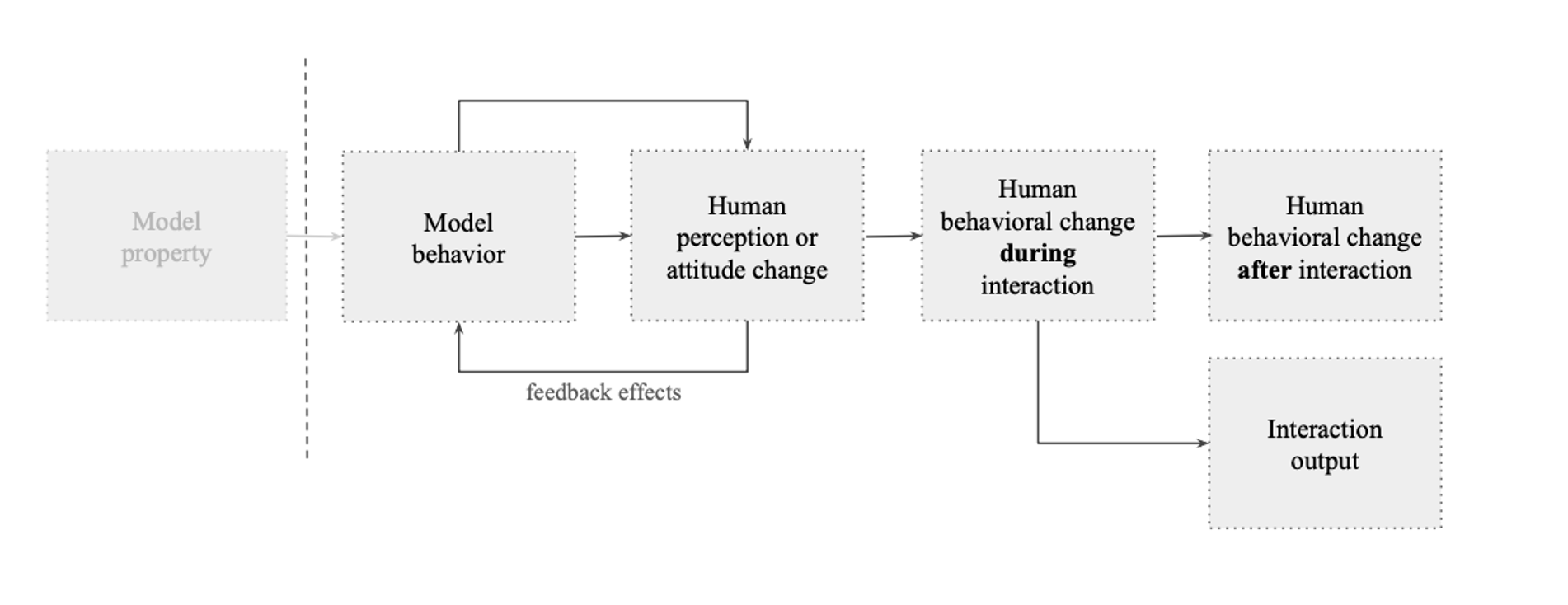

4.2 Principle 2: Identify the causal link between model behavior and human impact

To evaluate interaction harms in a valid way, we must trace how model behaviors influence human users. In Figure 2, we present an example of such a trace: underlying model properties shape observable model behaviors, which affect users through various pathways—from shaping moment-to-moment interactions to influencing deeper patterns of perception, decision-making, and behavior. Specifying the hypothesized pathways helps determine both what to manipulate in evaluations (model behaviors) and what to measure (human impact). We identify three key measurement targets:

Psychological impact: changes in user perceptions, attitudes and beliefs, and affective states

Behavioral impact: changes in user actions during and after interaction

Interaction outputs: quality and characteristics of the produced interaction artifact

Figure 2: Example of a causal trace showing how model properties may influence human behavior and human-AI interaction outcomes. Such traces help identify key measurement points for evaluation.

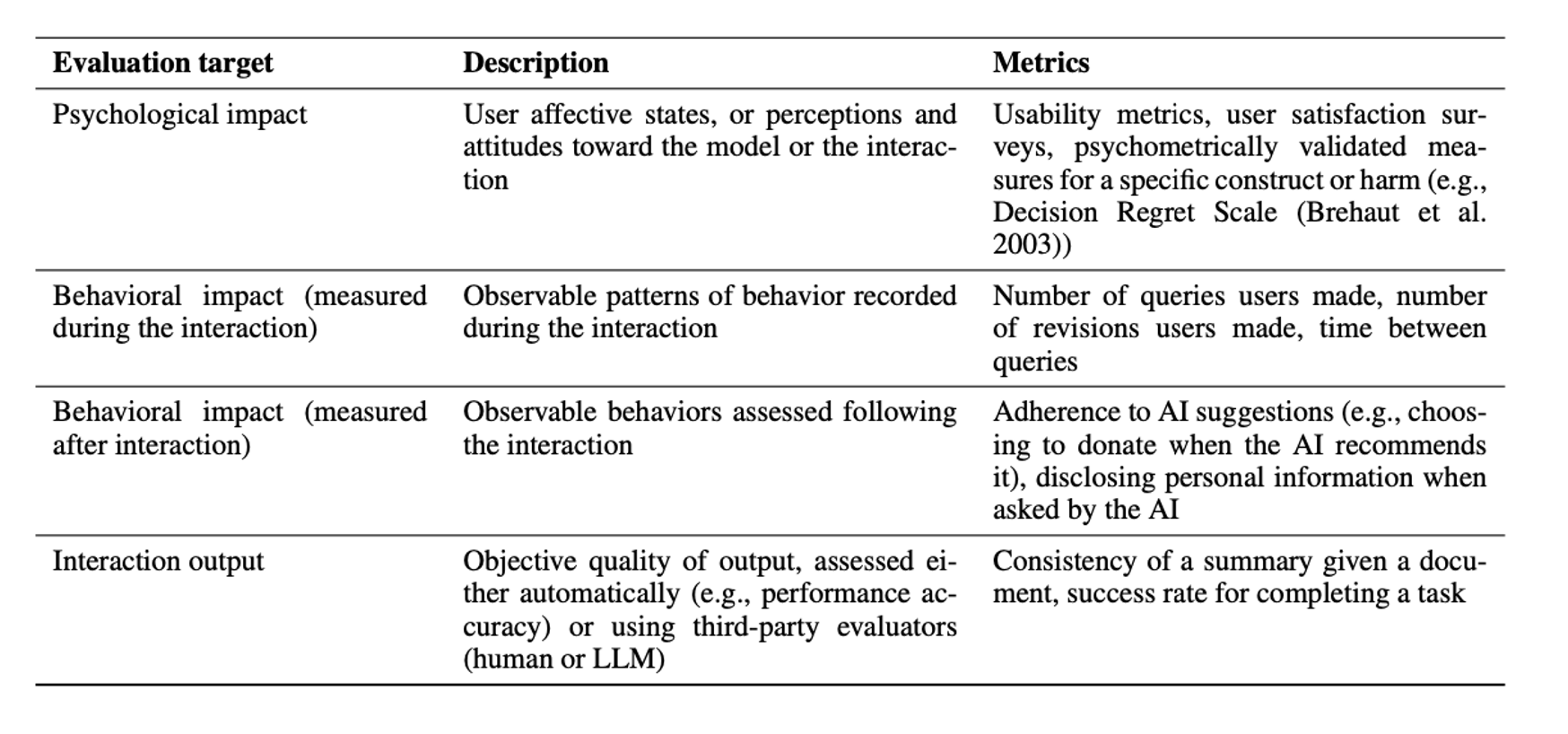

These measurement targets can be assessed through both self-reported measures—including validated scales for attitudes, perceptions, and affective states—and behavioral measures that track concrete actions like response time, task accuracy, and engagement patterns (Damacharla et al. 2018; Coronado et al. 2022; Gordon et al. 2021). In Table 2, we present a non-exhaustive set of these metrics for assessing both human impact and human-AI performance.

Table 2: Metrics to evaluate human-AI interactions

4.3 Principle 3: Structure human participation to balance validity and practicality

Evaluating human-AI interaction can involve varying degrees of human participation: from controlled studies with live participants, to analyses of chat logs between users and deployed systems, to automated user simulations. Each approach offers distinct trade-offs in terms of ecological validity, experimental control, cost, and ethical considerations.

Chat logs from real-world interactions provide unparalleled ecological validity and scale. These naturally occurring conversations capture authentic user behaviors and emergent patterns that would be difficult to replicate in controlled settings (Tamkin et al. 2024). The massive volume of existing logs also enables analysis of rare events and edge cases that controlled studies might miss. Recent work has paired analyses of millions of chat logs of user conversations with ChatGPT with longitudinal surveys of those users to examine emotional well-being, showing a path forward for using chat logs while also assessing real user impact (Phang et al. 2025). However, this observational data is often proprietary, difficult to access, raises serious privacy concerns, and may limit our ability to test specific hypotheses or establish causal relationships (Reuel et al. 2024; Zhao et al. 2024; Ouyang et al. 2023).

Controlled human subject studies, while more resource intensive, allow for the systematic examination of specific interaction patterns and outcomes. These studies are particularly valuable when we need to administer psychological measures or capture behavioral changes over time. However, their artificial nature and high costs make them better suited for targeted investigation of specific hypotheses rather than broad-scale evaluation.

Existing research on user simulations has utilized LLMs to simulate believable human behaviors using a range of architectures from demographic-based models to simulations informed by qualitative interviews (Park et al. 2024, 2023). Recent work has used such simulations to evaluate safety risks (Zhou et al. 2024), sometimes utilizing human experiments to validate the evaluations (Ibrahim et al. 2025). Such simulations can be particularly valuable for exploring scenarios that would be ethically challenging to test with real users. Unlike real human participants, who naturally shape conversations in diverse ways, simulations also allow for controlled trajectories, making it easier to analyze how interactions evolve across different scenarios. However, their limitations in believability, accuracy, and diversity require further study, as recent work has shown that they misportray and flatten representations of marginalized identity groups (Wang, Morgenstern, and Dickerson 2025; Agnew et al. 2024).

5. Open Challenges and Ways Forward for Interactive Evaluations

In this paper, we motivate the need to investigate human-AI interaction dynamics that current evaluations miss. However, implementing such evaluations at scale presents several concrete challenges. These range from ethical questions about studying potentially harmful interactions, to practical needs for research infrastructure, to methodological questions about producing actionable insights for stakeholders. While our design principles outline key considerations for scenarios, measurements, and participation strategies, advancing these methods requires addressing key open questions. Here, we identify specific challenges and opportunities where concentrated research efforts could significantly advance our ability to evaluate increasingly interactive AI systems.

5.1 How can we ethically work with human participants on studying harms?

When are user simulations appropriate replacements? Studying interaction harms poses inherent ethical challenges: we need to understand potentially harmful dynamics without exposing participants to those same harms. This requires careful consideration of when and how to involve human participants. For participant protection, AI researchers should adopt existing practices from fields experienced in providing adequate participant training, thoughtful debriefing, and active feedback collection to mitigate experimental harms (McKee 2024). Simulated human interactions offer a promising direction for studying scenarios where minimizing harm is challenging, such as young people’s interactions with AI systems or emotional attachment to AI systems. Recent work suggests these simulations can believably represent human behavior (Park et al. 2023, 2024), but more work is needed to understand how to best capture diverse user behaviors and develop ethical guidelines for deploying user simulations in safety evaluations (Agnew et al. 2024; Anthis et al. 2025).

5.2 How can we improve researcher access to data for understanding interaction harms?

Current public datasets of human-AI conversations, while valuable, fall short of meeting researchers’ needs. Large collections of chat logs like WildChat and ShareGPT, voluntarily contributed by users, offer millions of conversations but provide only a narrow window into AI usage, capturing self-selected interactions that may not represent typical user behaviors or patterns (Zhao et al. 2024; Ouyang et al. 2023). These datasets can be biased in terms of user demographics, use cases, and interaction styles, potentially leading to incomplete or incorrect conclusions about how people typically interact with AI systems. AI developers, such as large labs which provide commercial chatbot services, have access to the most comprehensive interaction data (Tamkin et al. 2024). While these labs have incentives to protect user privacy and proprietary information, developing privacy-preserving data sharing frameworks is necessary to enable researchers to access representative interaction data while maintaining user trust and consent.

5.3 What infrastructure do we need to facilitate interactive evaluations?

Many interactive evaluations share common stages: recruiting participants, collecting interaction data, and administering surveys and other tasks. Developing accessible protocols, guides, and standardized test suites—similar to those available for non-interactive evaluations—can support and facilitate an increase in interactive evaluations (UK AI Safety Institute 2024; METR 2024; Collins et al. 2023). Some existing platforms enable crowd-sourced interactive evaluations, but they face validity issues by gamifying safety testing (e.g., with tasks like ‘break the model in one minute’) and reducing safety to vulnerability against jailbreaking (Angelopoulos et al. 2024). Instead, we need more platforms that standardize the foundational elements of human subject studies with AI while maintaining scientific rigor, reducing technical overhead for researchers, and enabling broader participation in AI evaluation.

Additionally, current platforms primarily support single session studies, but understanding many interaction harms requires longitudinal evaluation capabilities with secure, privacy-preserving mechanisms for tracking behavioral changes over extended AI usage periods—a critical infrastructure gap that must be addressed to fully assess long-term influences of AI systems on human users.

5.4 How can interactive evaluations produce actionable findings that guide stakeholder decisions? What are the limitations of controlled studies in capturing broader impacts?

Randomized control trials (RCTs) have proven valuable for policy decisions by providing rigorous evidence, particularly in public health and social policy (Hariton and Locascio 2018). Similarly, interactive evaluations aim to produce actionable findings about how model behaviors influence human perception and behavior. These insights can help stakeholders make better decisions about model deployment, safety mechanisms, and interaction design. However, we currently lack adequate visibility into how different stakeholders—from AI labs to government bodies—actually use evaluation results in their decision-making processes. Bridging this gap requires closer collaboration between researchers and decision-makers to ensure evaluation designs align with practical needs (Hardy et al. 2024). Finally, we must be mindful of limitations; like RCTs, controlled evaluations of human-AI interaction may effectively measure individual-level effects (like individual manipulation or overreliance) while still missing broader systemic patterns. Thus, while measuring these individual impacts is crucial for understanding immediate safety concerns, they should be complemented with examinations of how AI systems reshape institutional structures, professional practices, and social arrangements—effects that emerge beyond individual interactions (Chater and Loewenstein, 2023).

6. Conclusion

As AI systems become increasingly integrated into our daily lives, moving beyond content risks to examine harms that emerge through sustained engagement is not just an academic exercise—it is essential for developing responsible technologies that prioritize human well-being. Our work makes three key contributions to this critical area: first, we motivate the need to attend to interaction harms and demonstrate why current evaluation paradigms systematically fail to capture them; second, we develop a structured framework of practical principles for designing interactive evaluations that draw from multiple disciplines; and third, we identify specific implementation challenges and research directions that must be addressed for these methods to succeed at scale. Several established industries, from medicine to automobiles, have long recognized the need to study their technologies' impact on users through extensive testing during development and after deployment (Wouters, McKee, and Luyten 2020). As AI capabilities and applications continue to expand, we must similarly strengthen our investment in understanding these systems’ effects on human behavior and society at large. The methodological considerations outlined here provide a foundation for this shift in how we evaluate increasingly interactive AI systems.

References

Agnew, W.; Bergman, A. S.; Chien, J.; Díaz, M.; El Sayed, S.; Pittman, J.; Mohamed, S.; and McKee, K. R. 2024. The illusion of artificial inclusion. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.08572.

Alberts, L.; Keeling, G.; and McCroskery, A. 2024. Should agentic conversational AI change how we think about ethics? Characterising an interactional ethics centred on respect. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.09082.

Angelopoulos, A.; Vivona, L.; Chiang, W.-L.; Vichare, A.; Dunlap, L.; Salvivona; Pliny; and Stoica, I. 2024. RedTeam Arena: An Open-Source, Community-driven Jailbreaking Platform. LMSYS Org Blog. Accessed: 2025-03-05.

Anthis, J. R.; Liu, R.; Richardson, S. M.; Kozlowski, A. C.; Koch, B.; Evans, J.; Brynjolfsson, E.; and Bernstein, M. 2025. LLM Social Simulations Are a Promising Research Method. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.02234.

Anthropic. 2023. Anthropic’s responsible scaling policy. https://www.anthropic.com/news/anthropics-responsible-scaling-policy.

Blodgett, S. L.; Lopez, G.; Olteanu, A.; Sim, R.; and Wallach, H. 2021. Stereotyping Norwegian salmon: An inventory of pitfalls in fairness benchmark datasets. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), 1004–1015.

Brehaut, J.; O’Connor, A.; Wood, T.; Hack, T.; Siminoff, L.; Gordon, E.; and Feldman-Stewart, D. 2003. Validation of a Decision Regret Scale. Medical decision making: an international journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making, 23: 281–92.

Chan, A., Salganik, R., Markelius, A., Pang, C., Rajkumar, N., Krasheninnikov, D., ... & Maharaj, T. (2023, June). Harms from increasingly agentic algorithmic systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (pp. 651-666).

Chang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhu, K.; Chen, H.; Yi, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. 2024. A survey on evaluation of large language models. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology, 15(3): 1–45.

Chater, N.; and Loewenstein, G. 2023. The i-frame and the s-frame: How focusing on individual-level solutions has led behavioral public policy astray. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 46: e147.

Chen, Y.; Wu, A.; DePodesta, T.; Yeh, C.; Li, K.; Marin, N. C.; Patel, O.; Riecke, J.; Raval, S.; Seow, O.; et al. 2024. Designing a dashboard for transparency and control of conversational AI. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.07882.

Collins, K. M.; Jiang, A. Q.; Frieder, S.; Wong, L.; Zilka, M.; Bhatt, U.; Lukasiewicz, T.; Wu, Y.; Tenenbaum, J. B.; Hart, W.; et al. 2023. Evaluating language models for mathematics through interactions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.01694.

Coronado, E.; Kiyokawa, T.; Ricardez, G. A. G.; Ramirez Alpizar, I. G.; Venture, G.; and Yamanobe, N. 2022. Evaluating quality in human-robot interaction: A systematic search and classification of performance and human-centered factors, measures and metrics towards an industry 5.0. Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 63: 392–410.

Costello, T. H.; Pennycook, G.; and Rand, D. G. 2024. Durably reducing conspiracy beliefs through dialogues with AI.

Damacharla, P.; Javaid, A. Y.; Gallimore, J. J.; and Devabhaktuni, V. K. 2018. Common Metrics to Benchmark Human-Machine Teams (HMT): A Review. IEEE Access, 6: 38637–38655.

Dev, S.; Sheng, E.; Zhao, J.; Amstutz, A.; Sun, J.; Hou, Y.; Sanseverino, M.; Kim, J.; Nishi, A.; Peng, N.; et al. 2021. On measures of biases and harms in NLP. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.03362.

Gao, J.; Gebreegziabher, S. A.; Choo, K. T. W.; Li, T. J. J.; Perrault, S. T.; and Malone, T. W. 2024. A Taxonomy for Human-LLM Interaction Modes: An Initial Exploration. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.00405.

Ghandeharioun, A.; Yuan, A.; Guerard, M.; Reif, E.; Lepori, M.; and Dixon, L. 2025. Who’s asking? User personas and the mechanics of latent misalignment. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 37: 125967–126003.

Gordon, M. L.; Zhou, K.; Patel, K.; Hashimoto, T.; and Bernstein, M. S. 2021. The Disagreement Deconvolution: Bringing Machine Learning Performance Metrics In Line With Reality. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’21. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9781450380966.

Hackenburg, K.; Ibrahim, L.; Tappin, B. M.; and Tsakiris, M. 2023. Comparing the persuasiveness of role-playing large language models and human experts on polarized US political issues. OSF Preprints, 10.

Hardy, A.; Reuel, A.; Meimandi, K. J.; Soder, L.; Griffith, A.; Asmar, D. M.; Koyejo, S.; Bernstein, M. S.; and Kochenderfer, M. J. 2024. More than Marketing? On the Information Value of AI Benchmarks for Practitioners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.05520.

Hariton, E.; and Locascio, J. J. 2018. Randomised controlled trials - the gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: randomised controlled trials. BJOG, 125(13): 1716. Epub 2018 Jun 19.

Hartvigsen, T.; Gabriel, S.; Palangi, H.; Sap, M.; Ray, D.; and Kamar, E. 2022. Toxigen: A large-scale machine generated dataset for adversarial and implicit hate speech detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.09509.

Hofmann, V.; Kalluri, P. R.; Jurafsky, D.; and King, S. 2024. AI generates covertly racist decisions about people based on their dialect. Nature, 633(8028): 147–154.

Handler, T. 2023. A Taxonomy for Autonomous LLM-Powered Multi-Agent Architectures.

Ibrahim, L.; Akbulut, C.; Elasmar, R.; Rastogi, C.; Kahng, M.; Morris, M. R.; McKee, K. R.; Rieser, V.; Shanahan, M.; and Weidinger, L. 2025. Multi-turn Evaluation of Anthropomorphic Behaviours in Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.07077.

Ibrahim, L.; Rocher, L.; and Valdivia, A. 2024. Characterizing and modeling harms from interactions with design patterns in AI interfaces. arXiv:2404.11370.

Jin, Z.; Heil, N.; Liu, J.; Dhuliawala, S.; Qi, Y.; Scholkopf, B.; Mihalcea, R.; and Sachan, M. 2024. Implicit personalization in language models: A systematic study. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14808.

Kuniavsky, M. 2003. In Observing the User Experience, xiii–xvi. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 978-1- 55860-923-5.

Lee, M.; Srivastava, M.; Hardy, A.; Thickstun, J.; Durmus, E.; Paranjape, A.; Gerard-Ursin, I.; Li, X. L.; Ladhak, F.; Rong, F.; et al. 2022. Evaluating human-language model interaction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.09746.

Li, N.; Pan, A.; Gopal, A.; Yue, S.; Berrios, D.; Gatti, A.; Li, J. D.; Dombrowski, A.-K.; Goel, S.; Phan, L.; et al. 2024. The wmdp benchmark: Measuring and reducing malicious use with unlearning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.03218.

Liao, Q.; and Sundar, S. S. 2022. Designing for Responsible Trust in AI Systems: A Communication Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, FAccT ’22, 1257–1268. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9781450393522.

Liao, Q. V.; and Xiao, Z. 2023. Rethinking model evaluation as narrowing the socio-technical gap. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.03100.

McCoy, R. T.; Yao, S.; Friedman, D.; Hardy, M.; and Griffiths, T. L. 2023. Embers of autoregression: Understanding large language models through the problem they are trained to solve. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.13638.

McKee, K. R. 2024. Human participants in AI research: Ethics and transparency in practice. IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society.

METR. 2024. METR Autonomy Evaluations Resources. https://metr.org/blog/2024-03-13-autonomy-evaluation-resources/

Mitchell, M. 2024. Ethical ai isn’t to blame for Google’s Gemini debacle.

OpenAI. 2025. Preparedness. https://cdn.openai.com/pdf/18a02b5d-6b67-4cec-ab64-68cdfbddebcd/preparedness-framework-v2.pdf

Ouyang, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, M.; Jiao, Y.; Iter, D.; Pryzant, R.; Zhu, C.; Ji, H.; and Han, J. 2023. The shifted and the overlooked: a task-oriented investigation of user-gpt interactions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.12418.

Park, J. S.; O’Brien, J.; Cai, C. J.; Morris, M. R.; Liang, P.; and Bernstein, M. S. 2023. Generative agents: Interactive simulacra of human behavior. In Proceedings of the 36th annual acm symposium on user interface software and technology, 1–22.

Park, J. S.; Zou, C. Q.; Shaw, A.; Hill, B. M.; Cai, C.; Morris, M. R.; Willer, R.; Liang, P.; and Bernstein, M. S. 2024. Generative agent simulations of 1,000 people. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.10109.

Parrish, A.; Chen, A.; Nangia, N.; Padmakumar, V.; Phang, J.; Thompson, J.; Htut, P. M.; and Bowman, S. R. 2021. BBQ: A hand-built bias benchmark for question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.08193.

Perez, E.; Huang, S.; Song, F.; Cai, T.; Ring, R.; Aslanides, J.; Glaese, A.; McAleese, N.; and Irving, G. 2022. Red teaming language models with language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.03286.

Phang, J.; Lampe, M.; Ahmad, L.; Agarwal, S.; Fang, C. M.; Liu, A. R.; Danry, V.; Lee, E.; Chan, S. W.; Pataranutaporn, P.; et al. 2025. Investigating Affective Use and Emotional Well-being on ChatGPT. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.03888.

Phuong, M.; Aitchison, M.; Catt, E.; Cogan, S.; Kaskasoli, A.; Krakovna, V.; Lindner, D.; Rahtz, M.; Assael, Y.; Hod kinson, S.; et al. 2024. Evaluating Frontier Models for Dangerous Capabilities. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.13793.

Raji, I. D.; Bender, E. M.; Paullada, A.; Denton, E.; and Hanna, A. 2021. AI and the everything in the whole wide world benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.15366.

Raji, I. D.; Kumar, I. E.; Horowitz, A.; and Selbst, A. 2022. The fallacy of AI functionality. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 959–972.

Reuel, A.; Bucknall, B.; Casper, S.; Fist, T.; Soder, L.; Aarne, O.; Hammond, L.; Ibrahim, L.; Chan, A.; Wills, P.; et al. 2024. Open problems in technical ai governance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.14981.

Rottger, P.; Pernisi, F.; Vidgen, B.; and Hovy, D. 2025. SafetyPrompts: a Systematic Review of Open Datasets for Evaluating and Improving Large Language Model Safety. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.05399.

Shelby, R.; Rismani, S.; Henne, K.; Moon, A.; Rostamzadeh, N.; Nicholas, P.; Yilla-Akbari, N.; Gallegos, J.; Smart, A.; Garcia, E.; et al. 2023. Sociotechnical harms of algorithmic systems: Scoping a taxonomy for harm reduction. In Proceedings of the 2023 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 723–741.

Staab, R.; Vero, M.; Balunovic, M.; and Vechev, M. 2023. Beyond memorization: Violating privacy via inference with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.07298.

Subramonyam, H.; Pea, R.; Pondoc, C. L.; Agrawala, M.; and Seifert, C. 2024. Bridging the Gulf of Envisioning: Cognitive Design Challenges in LLM Interfaces. arXiv:2309.14459.

Tamkin, A.; McCain, M.; Handa, K.; Durmus, E.; Lovitt, L.; Rathi, A.; Huang, S.; Mountfield, A.; Hong, J.; Ritchie, S.; et al. 2024. Clio: Privacy-Preserving Insights into Real World AI Use. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.13678.

The White House. 2023. https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/10/30/executive-order-on-the-safe-secure-and-trustworthy-development-and-use-of-artificial-intelligence/.

UK AI Safety Institute. 2024. Inspect AI.

UK Government. 2024. Ai Safety Institute approach to evaluations. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ai-safety-institute-approach-to-evaluations/ai-safety-institute-approach-to-evaluations.

Viegas, F.; and Wattenberg, M. 2023. The system model and the user model: Exploring AI dashboard design. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.02469.

Wallach, H.; Desai, M.; Cooper, A. F.; Wang, A.; Atalla, C.; Barocas, S.; Blodgett, S. L.; Chouldechova, A.; Corvi, E.; Dow, P. A.; et al. 2025. Position: Evaluating Generative AI Systems is a Social Science Measurement Challenge. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.00561.

Wang, A.; Morgenstern, J.; and Dickerson, J. P. 2025. Large language models that replace human participants can harm fully misportray and flatten identity groups. Nature Machine Intelligence, 1–12.

Weidinger, L.; Rauh, M.; Marchal, N.; Manzini, A.; Hen dricks, L. A.; Mateos-Garcia, J.; Bergman, S.; Kay, J.; Griffin, C.; Bariach, B.; et al. 2023. Sociotechnical safety evaluation of generative ai systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.11986.

Weidinger, L.; Uesato, J.; Rauh, M.; Griffin, C.; Huang, P.- S.; Mellor, J.; Glaese, A.; Cheng, M.; Balle, B.; Kasirzadeh, A.; et al. 2022. Taxonomy of risks posed by language models. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 214–229.

Wouters, O. J.; McKee, M.; and Luyten, J. 2020. Estimated Research and Development Investment Needed to Bring a New Medicine to Market, 2009-2018. JAMA, 323(9): 844– 853.

Zhang, Z.; Jia, M.; Lee, H.-P. H.; Yao, B.; Das, S.; Lerner, A.; Wang, D.; and Li, T. 2024. “It’s a Fair Game”, or Is It? Examining How Users Navigate Disclosure Risks and Benefits When Using LLM-Based Conversational Agents. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’24. ACM.

Zhao, W.; Ren, X.; Hessel, J.; Cardie, C.; Choi, Y.; and Deng, Y. 2024. WildChat: 1M ChatGPT Interaction Logs in the Wild. arXiv:2405.01470.

Zhou, X.; Kim, H.; Brahman, F.; Jiang, L.; Zhu, H.; Lu, X.; Xu, F.; Lin, B. Y.; Choi, Y.; Mireshghallah, N.; et al. 2024. Haicosystem: An ecosystem for sandboxing safety risks in human-ai interactions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.16427.

© 2025, Lujain Ibrahim, Saffron Huang. Umang Bhatt, Lama Ahmad, and Markus Anderljung

Cite as: Lujain Ibrahim, Saffron Huang. Umang Bhatt, Lama Ahmad, and Markus Anderljung, Towards Interactive Evaluations for Interaction Harms in Human-AI Systems, 25-13 Knight First Amend. Inst. (June 23, 2025), https://knightcolumbia.org/content/towards-interactive-evaluations-for-interaction-harms-in-human-ai-systems [https://perma.cc/HE9H-LML5].

Lujain Ibrahim is a Ph.D. candidate in social data science at the University of Oxford.

Saffron Huang is a research scientist on the Societal Impacts team at Anthropic.

Umang Bhatt is an assistant professor and faculty fellow at the the Center for Data Science at New York University.

Lama Ahmad is on the Policy Research team at OpenAI where she leads partnerships and research on the risks and the social impact of artificial intelligence.

Markus Anderljung is the Director of Policy and Research at the Centre for the Governance of AI.