Abstract

The rapid advancement and adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping power dynamics among key AI stakeholder groups. Capturing this shift requires a framework to assess various dimensions of power held by different players in the AI ecosystem. While previous work has explored AI power dynamics from theoretical and philosophical perspectives, little attention has been given to concretely measuring who is involved in and impacted by the shifting power dynamics, which dimensions of power are evolving over time, and to what extent. In this paper, we conceptualize the AI Power Disparity Index (AI-PDI): a composite indicator designed to measure and signal the changing distribution of power in the AI ecosystem. Drawing on interdisciplinary theories, we propose to aggregate several key dimensions of power in the index, including its bases, means, scope, and degree. While the primary contribution of this work is to conceptualize the index, we take an initial step toward operationalizing it: inspired by the Delphi method, we recommend a collaborative, expert-driven methodology to determine the specific form and content of the index. We envision the AI-PDI to serve as a critical resource for policymakers, researchers, and civil society to track evolving power dynamics around AI, encouraging informed dialogue and guiding long-term strategies for democratic and transparent development and use of the technology.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming society at an unprecedented pace, fueling concerns that it may disrupt the balance of power across social, economic, and political spheres (Varoufakis 2024). For instance, automation driven by AI disproportionately impacts low-income workers (Kelly 2024; Schellekens and Skilling 2024), while the capacity to develop and commercialize AI remains concentrated in a handful of global AI companies located primarily in high-income countries (Schellekens and Skilling 2024). Much of the existing work on AI-induced disparities has focused on the micro-level, localized impacts of the technology in specific sectors and use cases, including racial and gender biases in hiring algorithms (Dastin 2018), facial recognition systems for surveillance (Buolamwini and Gebru 2018), or predictive policing (Heaven 2023). While identifying unfairness and bias at the model and use case level is essential, focusing solely on such disparities risks overlooking the emergence of broader, macro-level power imbalances over time (Kasy and Abebe 2021).

As AI becomes more integral to the economy, impacting workflows and decision-making processes across a wide range of sectors (Singla et al. 2024), control over it consolidates power in the hands of a small number of actors, including large tech corporations, that have the resources to build, deploy, release, and shape the narrative around the technology, with virtually no requisite transparency and accountability (Bommasani et al. 2021). This shift creates power imbalances among AI stakeholders, eroding individual and community autonomy while enabling a small number of actors to conduct unprecedented surveillance and shape public opinion and behavior (Capraro et al. 2024; Varoufakis 2024).

Recent work has examined algorithmic power, emphasizing its diverse manifestations—from shaping social relationships to reconfiguring power dynamics and structuring social norms and institutions (Lazar 2023, 2024). Despite the growing concern surrounding and efforts characterizing AI driven power dynamics in both academic literature (e.g., Colon Vargas 2024; Lazar 2023, 2024) and beyond (e.g., UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) 2025), we currently lack an aggregate index, or set of indicators, specifically designed to monitor and track the shifts in power dynamics and disparities over time and across entities.

Arguments for an index. Why is an aggregate index of AI power disparities essential? We offer a normative and a pragmatic argument for this endeavor. First, the legitimacy of a democracy depends on the presence of institutions that diffuse power, enable participation, and foster reciprocal recognition. In a liberal, power-sharing society, checks and balances are essential to prevent any single group from attaining dominance (Allen 2023). Aggregate measures of democracy, such as V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy Project 2024), have been developed to keep track of how democratic every nation is and how these trends change over time. Today, AI is playing an increasing role in shaping decision-making, norms, and democratic governance in society. Thus, an aggregate index of AI-driven power dynamics, and in particular a measure of the disparities to which AI is giving rise, serves as a mechanism for foregrounding democratic values in the governance of AI.

Second, and from a pragmatic perspective, indices have proven to be transformative in shaping policy discourse and driving changes in a wide range of societal domains. In international relations and economics, for example, indices like the Human Development Index (HDI) (Sagar and Najam 1998) and the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) (U.S. Department of Justice 2024) are highly visible and influential because of their ability to distill complex, multidimensional concepts into a single, easy-to-interpret measure to guide decisions, track progress over time and regions, and facilitate comparisons. For instance, policymakers can use composite measures to identify lagging dimensions and decide where interventions are most needed. Indices can also serve as an effective means of communication to the public and other relevant stakeholders, raising awareness, attracting media coverage, and building consensus for action. In a similar vein, a dedicated index capturing AI-driven power disparities would provide policymakers, the technology sector, and the civil society with an essential tool to identify where imbalances are most severe, evaluate the impact of interventions, and hold powerful actors accountable.

Our proposal: the AI Power Disparity Index. In this paper, we propose the development of the AI Power Disparity Index (AI-PDI). Like other related indices, such as Stanford’s AI Index (Maslej et al. 2025), we envision the AI-PDI to be an aggregate measure, meaning that it extracts trends emerging from specific real-world observations to represent important dimensions of the concept at hand (Babbie 2020), in our case, AI-driven power. We conceptualize how this broad, abstract concept can be systematized (Chouldechova et al. 2024) and eventually translated into concrete metrics and indicators, to reveal current trends in AI-driven power disparities in a format that is accessible; trackable over time; and understandable to policymakers, academics, and the broader public. The AI-PDI is intended to be not only a diagnostic tool to capture and track the magnitude and direction of power imbalances, but also a catalyst for efforts to improve transparency of the AI ecosystem and democratize the development and use of the technology over time.

Our proposed approach and contributions. The core contribution of the present paper is to develop the conceptual framework underpinning the AI-PDI. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the Joint Research Centre (JRC)’s Handbook on Composite Indicators (2008) outlines the best practices for developing composite indices. (See Section 2 for an overview of the 10 steps recommended in the handbook.) Our focus in this work is on the first step, that is, developing a theoretical framework for the index. We begin by providing an overview of prominent theories of power, the relationship between AI and power, and recent developments in algorithmic accountability (Section 2). We then elaborate on the definition and dimensions of power we propose to underpin the AI-PDI (Section 3). We enumerate the key actor groups in the AI ecosystem that the index should capture and characterize, in broad strokes, the variety of power dynamics these actors are involved in (Section 4). In particular, we outline several important dimensions of power for each actor group, propose example indicators for each dimension, and discuss where AI power disparities appear to be arising today.

While the primary contribution of this work is to conceptualize the AI-PDI, in Section 5, we outline our recommendation for operationalizing the index in the near future. In particular, we propose a collaborative process, inspired by the Delphi method (Linstone, Turoff et al. 1975), where facilitators conduct a series of surveys, interviews, and focus groups to gather iterative feedback from a diverse set of AI stakeholders, including AI researchers and practitioners, economic experts, policymakers, technology companies, and civil society representatives, to determine the final design and implementation of the index.

Broader implications. While by nature, an index like the AI-PDI cannot capture every nuance of AI-driven power dynamics, we envision it to provide a practical, communicable, and comparable tool to inform AI policy priorities, track progress, and hold actors accountable. In the past, indices like HDI have succeeded in broadening the lens of economic policymaking beyond growth-focused metrics, income, and wealth (Sagar and Najam 1998). Similarly, our hope is that the AI-PDI will expand the discourse around AI beyond capability and adoption (Maslej et al. 2025; Oxford Insights 2025; Cisco 2025) drawing attention to concerning shifts in the distribution of influence and control over the technology and its impact on humanity. Within the field of AI ethics, accountability is often framed either as a normative virtue—a willingness to be held to account—or as a mechanism—a set of practices and institutions that operationalize the process of being held to account. We contend that a prerequisite to either form is the capacity to generate an account. By systematically documenting disparities in power among AI actor groups, the AI-PDI creates the conditions under which ethical questions of accountability can meaningfully arise. Through making power legible—and thereby contestable—the AI-PDI lays the groundwork for a more just and inclusive AI ecosystem.

2. Related Work

In this section, we overview the relevant literature on foundational theories of power, algorithmic and AI-related power, as well as algorithmic accountability to ground our conceptualization of the AI-PDI (Section 2.1). We then overview indexing, best practices for creating indices, and expert elicitation methods, such as the Delphi method, to operationalize them (Section 2.2).

2.1 Power and AI

Theories of power. Power has been a fundamental focus of discussions in the social sciences for decades. While there is widespread agreement that power is important to study, there is notably less consensus on how to define and conceptualize power (Baldwin 2016). Max Weber (1925) defines power as “any change within a social relation to impose one’s will also against the resistance of others, independently of what gives rise to this chance” (Guzzini 2017). This definition serves as the inspiration for Robert Dahl’s more formal definition of power proposed in 1957: “A has power over B to the extent that he can get B to do something that B would not otherwise do.” (Guzzini 2017; Dahl 1957). Subsequent critiques by Bachrach and Baratz (1962) and Lukes (2012) argue that there were two additional “faces” of power: non-decision-making power, referring to the ability to suppress debate and limit the scope of what is considered possible within a particular domain, and preference-shaping power, referring to the ability to mold how people think, act, and perceive their environment, often to the point where individuals or groups accept certain decisions as inevitable or natural.

Berger (2005) organizes power into “power over,” “power with,” and “power to,” where power over refers to “a traditional dominance model where decision making is characterized by control, instrumentalism, and self-interest”; power to represents “forms of resistance that public relations practitioners may use to try to counter a dominance model”; and power with relations reflect “an empowerment model where dialogue, inclusion, negotiation, and shared power guide decision making.” In international relations, scholars like Nye (2004) have categorized power according to hard and soft power, where hard power refers to the ability to influence others through coercion, force, or economic pressure, while soft power operates through attraction and persuasion, shaping preferences through culture, diplomacy, and ideology. Due to the ever-present disagreements in defining and subdividing power, Haugaard (2010) argues that power is a “family resemblance concept,” meaning that there is no single “best” definition of power. Some members of the power “family” include “episodic power,” which is “the exercise of power that is linked to agency”; “dispositional power,” which is the inherent capacities that an actor may have regardless of whether the actor exercises these capacities; and “systemic power,” which is the way in which social systems create differences in dispositional power among different actors. In the AI-PDI, in line with previous discussions on algorithmic power (e.g., Lazar 2024), we limit our focus to “power over” and episodic power.

Algorithmic power. Previous work has studied how algorithms exert power. Diakopoulos (2015) argues that algorithms exercise power through prioritization, classification, association, and filtering. Beer (2019) considers the social power of algorithms, including their power to diminish human agency, make decisions, and create norms. Latzer and Festic (2019) provide a user-centric perspective on evaluating algorithmic power, proposing a theoretical model for understanding the significance of algorithmic governance in everyday life. They argue that empirical assessments of algorithmic power can be developed using their theoretical model by using mixed-methods approaches.

Other work has studied how algorithms, AI, and technology at large shift existing power dynamics between different actors. Waelen (2024) uses Haugaard’s definition of power as a family resemblance concept to explore the power shifts caused by computer vision, while Sattarov (2019) uses Haugaard’s definition to explore power shifts in technology more broadly. Lazar (2023) argues that algorithmic systems shape social power relations in three main ways: by allowing technology companies to have power over civil society, shaping relations between people using the algorithmic system, and by changing broader societal structures. He argues that overall, AI further concentrates power toward a small group of actors. Waelen (2022) asserts that the field of AI ethics should be understood in terms of how it changes the power relations between stakeholders.

In the AI-PDI, rather than considering the power of various algorithms themselves (Diakopoulos 2015; Beer 2019; Latzer and Festic 2019), our goal is to capture the power of various AI actor groups who, actively or passively, shape these algorithms and the systems in which they are embedded. Although previous work has already explored the influence of AI in shaping power dynamics through a philosophical lens (Waelen 2024; Lazar 2023; Sattarov 2019), our aim is to create a composite index of AI-driven power disparities.

Algorithmic accountability. Algorithmic accountability is a central issue in AI ethics and governance scholarship. There are two interconnected ways of thinking about algorithmic accountability (Bovens 2010): The first view considers the willingness to be held to account for algorithmic systems as a virtue and sets normative expectations around how individuals and systems should behave and operate in the world (Nissenbaum 1996; Diakopoulos 2015; Kroll et al. 2017). The second view explores the mechanisms through which a system is held to account, through power relations between differently-positioned parties (Metcalf et al. 2021, 2023; Selbst 2021; Wieringa 2020). While the first approach has been foundational to AI ethics discourse in the United States, the second approach has been central to scholarship in the European Union, Canada, United Kingdom, and Australia (Aucoin and Heintzman 2000). Accountability requires producing an account to explain or make sense of actions (Metcalf et al. 2023). Thus, the act of producing such an account is a necessary precondition for ethical discussions on holding those who produce it accountable.

We commit to an expanded view of accountability—not just as a retrospective obligation to justify decisions, but as an ongoing capacity to participate in arrangements to share power. In our view, accountability is not only a property of an actor, but a feature of the relationship between actors within institutional settings that support acts of justification, challenge, and reform. Thus, measuring power disparities through the AI-PDI becomes foundational to the very possibility of relational accountability in the AI ecosystem.

2.2 Indices and AI

Overview of indices. Indices are composite measures that summarize relevant real-world observations to represent the key dimensions of the concept at hand (Babbie 2020). Indices have been beneficial in summarizing multidimensional concepts to support decision makers, allowing people to compare complex dimensions, and facilitating communication with the general public (Joint Research Centre 2008). Indices commonly utilize survey research and other quantitative methods (Babbie 2020).

Best practices for creating indices. Poorly constructing or misusing an index may send misleading policy messages, invite simplistic conclusions, or obscure failures (Joint Research Centre 2008). Consequently, the OECD and the JRC (2008) have constructed a handbook to guide the construction and use of indices. In particular, the handbook recommends a ten-step process for constructing indices, consisting of (1) developing a theoretical framework, (2) data selection, (3) imputation of missing data, (4) multivariate analysis, (5) normalization, (6) weighting and aggregation, (7) uncertainty and sensitivity analysis, (8) back to the data (to retroactively analyze how the selected data and indicators are affecting the index), (9) links to other indicators, and (10) visualization of the results.

Power-centric indices. Existing power-related indices include the Soft Power 30 (Portland Communications), the Lowy Institute Asia Power Index (Lowy Institute 2019), and the Power Distance Index (Hofstede 1984). Defining a good measure of power, however, is a difficult task that has been thought about for a long time (Baldwin 2016). Some common pitfalls with measuring power are beginning with an incomplete conception of power, measuring power as a one-dimensional concept (that is, a single number), and simplifying power into resources (such as money) (Baldwin 2016).

AI-centric indices. Several AI-related indices have been proposed in recent years. Stanford’s AI Index (Maslej et al. 2025) provides a comprehensive report that covers essential economic trends related to AI. The index contains a “Global AI Vibrancy Tool” that provides a score for each country each year based on eight pillars: research and development, responsible AI, economy, education, diversity, policy and governance, public opinion, and infrastructure. AI readiness indices determine how prepared governments (Oxford Insights 2025; UNESCO 2023) or companies (Cisco 2025) are to integrate AI into the delivery of their services. The Anthropic Economic Index (Handa et al. 2025) provides a report aimed at understanding the effects of AI on labor markets and the economy over time. The Foundation Model Transparency Index (Bommasani et al. 2023) assesses the transparency of foundation models using 100 indicators designed to capture upstream resources, model characteristics, and downstream use. While not an index, Ecosystem Graphs (Bommasani et al. 2024b) aims to characterize the sociotechnical impact of foundation models in an understandable format, where nodes represent assets (datasets, models, applications) and edges represent dependencies (technical relationships between assets that induce social or economic relationships between organizations).

Our proposed AI-PDI is intended to complement existing AI-related indices. While previous work focuses on AI as a technology (Maslej et al. 2025), AI readiness (Oxford Insights 2025; Cisco 2025; UNESCO 2023), or the AI economy (Handa et al. 2025), we focus on AI’s effect on reshaping macro-level power dynamics in society. Furthermore, while most indices capture phenomena at the level of countries, markets, or companies, our index is aimed at capturing power dynamics at the level of major AI actors. To address some of the weaknesses of existing power measures, we build the AI-PDI on a clear conception of power, proposing a multi-dimensional view of it that addresses non-resource-based dimensions of power, such as the means that one actor has to exercise power over another. To adhere to existing best practices, we follow the ten steps outlined in the OECD and JRC Handbook (2008) focusing on the first step of this process, that is, developing the theoretical and conceptual framework for the index.

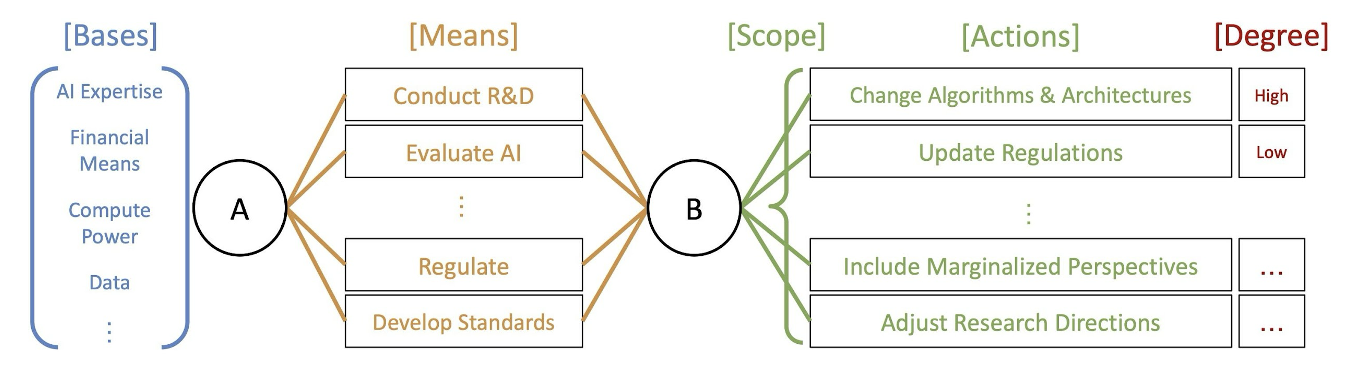

Figure 1: The dimensions of the power relation between actor A and actor B. On the left, a set of bases, or resources, available to A is shown. A is represented as a circle connected to another circle, B, through the orange lines that represent the means A can use to influence B. B is then connected to a set of actions through green lines. These actions represent the outcomes available to B as a result of the means used by A and depict the specific aspects of B’s behavior that A can impact through its actions. The red text represents the degree, or probability, of each action being taken. The purple text represents the cost to actor A to influence actor B, and the pink text represents the cost to actor B to refuse actor A's attempt to influence actor B's behavior. Note that the domain would be included by counting the number of actors B that are considered.

Expert elicitation. The OECD and the JRC (2008) envision the involvement of experts and stakeholders in the development of a theoretical framework for an index. There are numerous structured techniques used for eliciting experts' judgment, including focus group discussions, the nominal group technique, and the Delphi method (Mukherjee et al. 2018). Each technique has advantages and disadvantages; for example, if not carefully facilitated, focus group discussions may result in groupthink, where the desire for group harmony leads to a decrease in individuals’ independent critical thinking (Janis 2008).

While our core contribution for this paper is the conceptual framework of the AI-PDI, we outline a detailed recommendation to use the Delphi method to operationalize the PDI in Section 5. We recommend choosing experts from each of the key AI actor groups we identify, such as technology companies, academia, and civil society. The Delphi method “[structures] a group communication process so that the process is effective in allowing a group of individuals, as a whole, to deal with a complex problem”(Linstone, Turoff et al. 1975). There are four main criteria that characterize the Delphi method: anonymity, iteration, controlled feedback, and statistical group response (Von Der Gracht 2012). We recommend the Delphi method over other methods for expert elicitation since it has the key advantages of mitigating groupthink, the halo effect (individuals’ opinions being influenced by factors unrelated to the topic at hand, such as charisma), and the dominance effect (individuals who are perceived to be dominant have more influence in the group decision) (Mukherjee et al. 2018). Mitigating these biases is especially important since the topic of discussion is power, and the participating experts will have widely varying degrees of power over each other. For example, the perceived expertise of participants from technology companies and academia can prevent representatives of civil society from voicing their true opinions, even though input from civil society is equally valuable as input from technology companies or academia in the construction of such an index.

3. Systematizing the Concept of Power: Definition and Dimensions

In this section, we provide a formal definition of power and utilize existing philosophical frameworks to identify the key dimensions of power. We then discuss how this framework can underpin the AI-PDI.

Definition of power. Our goal with the AI-PDI is to highlight “episodic power,” or, “power over.” In this vein, we use the definition of influence outlined in Modern Political Analysis (Dahl and Stinebrickner 2003) as “a relation among human actors such that the wants, desires, preferences, or intentions of one or more actors affect the actions, or predispositions to act, of one or more actors in a direction consistent with—and not contrary to—the wants, preferences, or intentions of the influence-wielders.” Note that we use the definition of influence from Dahl and Stinebrickner (2003) instead as they use this term to refer to what other political scientists often call "power" (Dahl 1957; Stinebrickner 2015). In this definition, power is fundamentally a relationship between two actors (Lazar 2024). Therefore, it is futile to develop a single, absolute power measure that comprehensively describes an entity’s power over a variety of other actors (for example, a single number representing technology company’s ‘total power’ over governments, organizations, individuals, and communities) (Baldwin 2016). Instead, we propose to characterize power between any two entities across multiple dimensions.

The dimensions of power. In accordance with the idea that power is a relationship between two actors, we consider pairwise relationships between actor A and actor B in the AI-PDI. In our case, the actors A and B could, for example, represent a technology company (A) and an academic institution (B). We rely on Robert Dahl’s (1957) framework to analyze these relationships. He broke the concept of power into four key dimensions to analyze the power that an actor A has over an actor B (denoted as A → B). The four dimensions, along with illustrative examples applicable to AI power dynamics, are as follows:

- A’s bases of power. Bases are the resources, opportunities, actors, objects, and beyond that A can exploit to exert power over B. (By themselves, the bases are inert and passive.) In the context of AI power dynamics, A could represent a technology company who has the bases of data and finances.

- A’s means of exploiting their bases to affect B. These are the different ways A can attempt to influence B. For example, in the context of AI power dynamics, A could represent a national government, which can pass laws (the means) that force B, a technology company, to take certain actions.

- B’s scope. These are the aspects of B’s behavior that can be affected by A. For example, in the context of AI power dynamics, A, a social media company, could change the political beliefs (part of the scope) and emotions (part of the scope) of B, a member of civil society.

- For each response s in B’s scope, there is a corresponding degree. This is the extent to which A can change the probability/propensity of B taking action s. (Note that Dahl (1957) uses the word “amount” in his work instead of “degree.”)

There are other dimensions of the power that an actor A has over an actor B that we can add to the above set of dimensions (Dahl 1957; Harsanyi 1962). - The domain of A’s power, which is the number or importance of other actors subject to an actor A’s power.

- The domain of A’s power, which is the number or importance of other actors subject to an actor A’s power.

- The costs to A, that is, whether it is costly or cheap for A to influence B.

- The costs to B, that is, whether it is costly or cheap for B to comply with A’s demands.

Figure 1 presents these dimensions of power. Note that the domain is implicitly included in the number of actors B that are considered. We note that Dahl’s framework for power can be further expanded to include additional perspectives provided by Dahl’s critics (Baldwin 2016), most notably by Bachrach and Baratz (1962) and Lukes (2012).

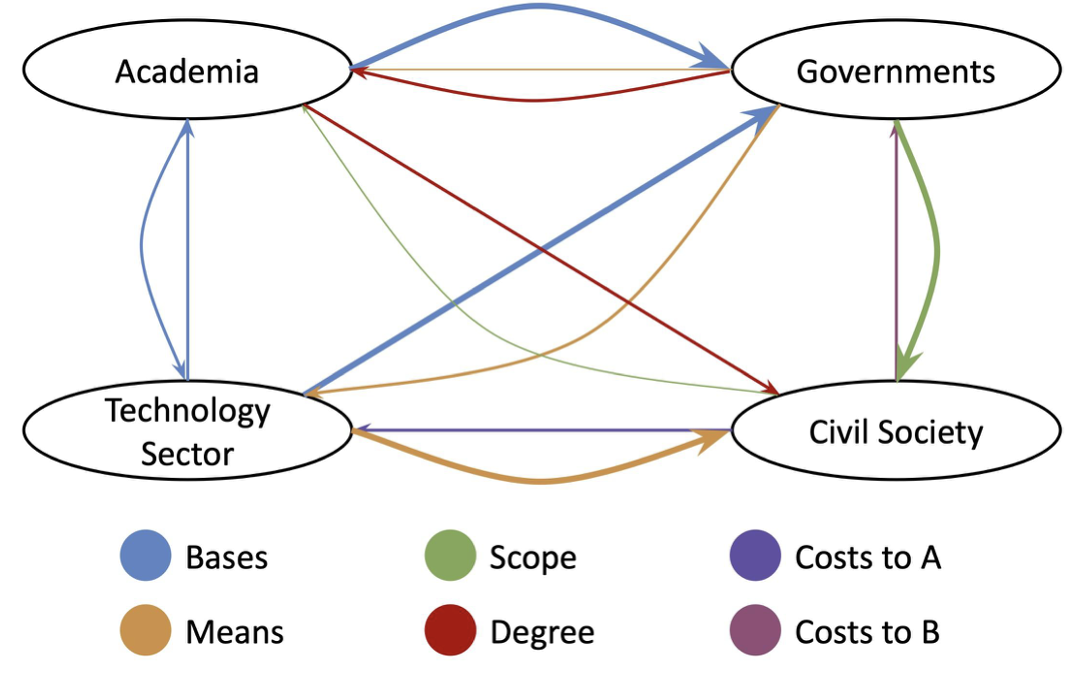

Our proposed systematization. Using this framework, for every actor A who influences actor B, we propose characterizing A’s power as a vector with the following dimensions: (bases, means, scope, degree, cost to A, cost to B). Figure 2 shows an example of how the pairwise relationships between each actor A and B form a network of power relations.

To understand an actor A’s “total power” over multiple actors, we can aggregate the power vectors for each relationship A → B. For example, by comparing a technology company with a national government, a university, and other entities, we could, in theory, aggregate these pairwise relationships to derive an overall power profile for the technology company. That said, following previous critiques of measuring power as a one-dimensional construct (Baldwin 2016), it is important to note that the different dimensions of power may not be comparable and commensurate with one another. For instance, one pairwise relationship A → C can show greater strength in the bases while another relationship B → C may be characterized as superior means. Our systematization is consistent with both component-wise comparisons and a more aggregative approach.

Figure 2: Example diagram visualizing the potential output of the AI PDI. The nodes/circles represent major AI actor groups. The arrows between each pair of actors A and B represent the power relationship between the two actors. The arrow direction A → B represents A’s power over B. The color of the arrow represents the dominant dimension of power. The thickness of the arrow represents the strength of that dimension of power, with thicker arrows indicating more strength. Note that this is only an illustrative diagram; The final index could divide the ‘Technology Sector’ node into 10 different nodes, for example with each representing a salient actor in the technology sector.

Conceptualizing the Index

The AI-PDI is meant to capture the power disparities among major actors groups using the systematization proposed in the previous section. In this section, we propose four major actor groups that at the very least must be addressed by the index, and we characterize the dimensions of the power they hold over one another using several examples.

4.1 Key AI Actor Groups

The AI-PDI will need to identify key AI actor groups; as a starting point, we identify four key AI actor groups in Table 1 and provide a broad-strokes characterization of the power afforded to each one. These actor groups are not meant to be exhaustive and may not capture the full complexity of the power relations in the AI ecosystem. In particular, we acknowledge that, none of the actor groups presented here are monolithic: for example, the actor group ‘Technology Sector’ contains both large corporations and small technology startups, which have different power profiles. The identification of the key actor groups will be a key component of the operationalization of the index, which we elaborate on in Section 5.

As outlined in Table 1, each AI actor plays a different set of roles in the AI ecosystem, depending on data, computing power, finances, and expertise, among other factors. Data forms a key foundation for AI models, and actors who control large, high-quality datasets have a clear advantage in developing advanced models (Suntsova 2024). Computing power, including access to fast hardware or cloud services, determines the pace of technology development and distribution. Financial resources allow actors such as governments, academia, and technology companies to advocate for their desired ends.

There are also many intangible factors—beyond just resources—that influence how AI actors operate. For example, legal frameworks and regulations both shape what actors can do and allow certain actors to shape what other actors can do. Connections between AI actors give certain actors the advantage of sharing knowledge and working together to set standards, while disadvantaging other actors. Understanding both who is involved in the AI ecosystem and what gives rise to AI-related power helps consolidate the key elements necessary for a holistic index of AI-driven power disparities.

4.2 Characterizing the Power of Each Actor

Using our philosophical framework of power in Section 3 and the AI actor groups identified above, we next provide an initial characterization of the power of each actor. In particular, we expand on the indicators that are important to each group of actors, classifying the indicators into bases, means, scope and degree. We also highlight where there are increasing disparities. We emphasize that the analysis provided in this section is meant only as a starting point, to highlight major elements of power each AI actor group holds and illustrate how our conceptual framework allows for a structured understanding of these elements.

Academia. Academia has a key base in its position as an education provider and research producer. This allows academia to have the means to train new generations of AI researchers, shape peer review, and determine scientific priorities. Indeed, top academic institutions have produced many of the founders, lead researchers, and influential thinkers in industry AI labs. In this manner, academia exerts power over the technology sector. The degree depends on the extent to which the technology sector adopts academia's teaching and research priorities.

Civil Society. Civil society, including its representatives in the form of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), has bases such as data ownership, public attention and pressure, expertise in policy and governance, and in some cases, financial means. These bases allow civil society to have the means to audit, contest, and litigate against AI systems (Katell et al. 2020; Richardson, Schultz, and Southerland 2019). In this manner, civil society can exert power over the technology sector. Through advocacy and standard setting, civil society and NGOs can influence the technology sector and academia by promoting actions such as adhering to standards and directing research agendas to study these standards (Schiff et al. 2021). If successful, the actions within these groups’ scope all have high degree of influence and can carry significant impact.

Technology Sector. The technology sector’s bases include financial resources, data, compute, highly-capable AI models, and AI expertise. Financial resources allow the technology sector to have power over academia through means like attracting talent (Scheiber 2016), providing funding for research, and access to state of the art AI models. Data and compute also allow the technology sector to have power over academia through means such as innovation, research, and development (Ahmed and Wahed 2020). Highly-capable AI models allow the technology sector to have power over civil society through the means of model use. This power relation can make members of civil society take a wide scope of actions which vary from using AI-generated search results to inflicting harm on oneself and others (Payne 2024). The degree varies widely for different actions in the scope. AI expertise and financial means allow technology companies to have power over government through the means of “[shaping] the science, morality and laws of artificial intelligence” (Benkler 2019). One action in the scope of the technology sector’s power over the government is encouraging the government to pass laws that are favorable for the sector (McKeown 2024).

Table 1: An overview of key AI actor groups and a broad-stroke characterization of their power.

|

Group |

Description |

Characterization of Power |

|

Academia |

Scholars from fields such as computer science, sociology, political science, and ethics. |

Educate AI experts. Evaluate AI systems. Research AI innovations. Develop standards. |

|

Civil Society |

The public at large, including various interest groups, non-marginalized and marginalized communities, and NGOs. |

Consume technology. Own and provide data. Influence the AI narrative. Demand accountability. |

|

Technology Sector |

Technology corporations and start-ups, including their senior executives, data scientists, and AI experts. |

Develop AI. Purchase data and compute. Sell AI. Influence the AI Narrative. Fund Research projects. Evaluate AI. |

|

Government |

Officials from national and local government groups involved in technology procurement, policy, and regulation. |

Regulate AI. Procure AI. Oversee AI. Fund research projects. Consume AI. Set norms and standards. |

Governments. Governments have the bases to purchase and procure AI. They also have the means to pass laws and regulations, thus having power over technology companies (Dor and Coglianese 2021). Governments also have the means to set norms and standards surrounding AI systems (Feldstein 2024). Similar to the case of litigation in the power relation between civil society and technology companies, the actions within the technology sector’s scope are very impactful in the power relation between governments and the technology sector. Furthermore, many of the actions could have a high degree of influence.

Where AI power disparities are emerging. How do we use the initial analysis above to determine where AI power disparities are emerging or worsening? One way is to analyze the major AI-related changes in recent years. Some of the most notable trends include drops in hardware costs, growing private investment in AI research and development, and the wide availability of highly capable models (Maslej et al. 2025). These trends all represent changes to important bases of power for the actors involved, in particular, the technology sector. Thus, we see that the biggest disparities primarily occur between the technology sector and other AI actor groups, with the technology sector gaining power. Our conceptual framework allows for a formal, rigorous, and structured analysis of power disparities—a formative step toward quantifying these disparities as part of the AI-PDI.

5. Proposed Methodology for Operationalizing the Index

While in the previous section, we highlighted some of the major sources of power for each of our four actor groups, operationalizing the index requires extending this analysis to all relevant AI actors; every pairwise power relation; and all relevant bases, means, actions in the scope, degrees, domain, and associated costs to actors A and B. While the core contribution of this work is conceptualizing the AI-PDI, in this section, we propose a methodology for translating the framework into an operational index.

Comparable projects in other domains, such as the V-Dem project (Varieties of Democracy Project 2024), have been operationalized using expert input. Similarly, to operationalize the AI-PDI, we recommend using a variation of the Delphi method (Linstone, Turoff et al. 1975) to gather structured insight from representatives of each AI actor group. This method is especially useful for complex and interdisciplinary topics (Grisham 2009), including AI power disparities. A process like the Delphi method helps the group move toward a shared understanding without risking groupthink.

5.1 Key Topics of Inquiry

The goals of the Delphi method should be to arrive at a consensus on the following topics:

- The breakdown of AI actor groups captured by the index.

- Key dimensions of power that should be characterized for each power relationship between AI actors.

- For each power dimension of the relation A → B, the suitable indicators and levels of granularity required for measurement.

- Identifying appropriate sources of data to measure each indicator, and strategies for handling missing data.

- Strategies to assess whether measures are comparable across each dimension of power and between actor groups.

- The target audience for the index and the most useful output format(s).

- Recommendations on who should be responsible for measurements and reporting and how frequently reports should be updated and published.

Facilitators can use these questions as a starting point to elicit feedback from participants. Participants’ expert responses to the above questions will facilitate operationalizing the index in a manner that is theoretically sound and practically viable.

5.2 Elicitation Methodology

In the following paragraphs, we outline some of the key aspects of the method we recommend to elicit expert feedback and consensus.

Recruitment procedure. We recommend recruiting a diverse group of participants from industry, academia, government, and representatives of civil society. This group should cover a wide range of AI expertise and experience. For instance, academic participants should represent relevant disciplines (e.g., sociology, economics, computer science, philosophy, law, and policy). To compile the group of participants, we recommend using several approaches. Facilitators can seed a snowball sampling method using their existing social and professional networks. Once a starting set of participants is gathered, snowball sampling can continue until adequate coverage is reached.

Arguably the most important step of the Delphi method is choosing the appropriate experts (Okoli and Pawlowski 2004), and by employing snowball sampling, the initial sample can easily be non-representative of the AI landscape and over-representative of individuals with views similar to those on the facilitating team. Thus, we recommend working with the initial group of experts found through snowball sampling to augment the selection of participants with a complementary group of experts to balance potential biases. For example, if the initial sample yields a high number of experts from large technology companies and a low number of experts from small technology companies, the participant selection should be augmented by deliberately selecting more participants from small technology companies. Using more diverse channels in the second round of recruitment, such as academic networks, professional organizations, government agencies, NGOs, and open public calls, will enable the facilitators to capture a wider range of perspectives that span technical, policy, and social dimensions.

Design and format. The Delphi method should consist of a series of surveys, questionnaires, and interviews with experts, following best practices from previous research (Rowe and Wright 1999). These rounds should be repeated until there is stability in the participants’ responses.

Round 0 can be an open-ended brainstorming session on the broad idea of an AI-PDI and what such an index should capture (Khodyakov 2023). This round allows participants to express their thoughts without being biased by the existing work. The goal in Round 0 should be to confirm with the experts that the general approach for the AI-PDI is valid and feasible, and that the high-level output is well defined. Facilitators should use this round to modify the conceptual framework for the index and topics highlighted in the previous subsection according to the feedback received from the participants.

In Round 1, facilitators should ask participants questions related to the topics outlined in Section 5.1. For example, when discussing the topic of suitable indicators for each dimension of power, facilitators can ask participants in one actor group (e.g., the technology sector) to reflect on their relationships with other actor groups (e.g., academia, civil society, and governments).

After each round, the facilitating team should provide a summary of the ideas brought up, including the level of support for each idea. This summary should be presented to the participants in the next round, allowing participants to refine their inputs based on previous feedback. The process of gathering expert input, summarizing the results, and presenting them to the experts should continue until there is stability in the participants’ responses.

5.3 Final Operationalization of the Index

After concluding the above process, the organizing team should analyze the feedback and propose an operationalization for the index that captures the feedback received. Following the analysis, the team should share the proposal with the participants for final feedback before moving forward with publishing the resulting index. Upon finalizing the theoretical framework and data selection, the organizing team should proceed through the next steps in building the AI-PDI following the ten steps and best practices outlined by the OECD and the JRC (2008), seeking additional expert feedback as appropriate.

Overall, our recommended methodology for operationalizing the AI-PDI is designed to be collaborative and iterative, incorporating expert judgment at both a broad conceptual level and within specific choices relevant to the particular dimensions of power, power relations, and measures. With a careful recruitment strategy, structured questionnaires, iterative feedback mechanisms, and focused analysis, our recommendations aim to encourage a rigorous operationalization of the AI-PDI.

6. Discussion

In this section, we discuss several additional considerations around the operationalization, measurement, and reporting of the index.

Output format. We envision the AI-PDI to contain three complementary findings: (1) a comprehensive power profile for each AI actor quantifying the key elements of their power over all the other actors, (2) a set of quantified assessments for each pairwise relationship between actors (where each number in the set represents the different dimensions of power), and (3) a report that describes the underlying nuances behind the assessment. Other indices (e.g., Varieties of Democracy Project 2024; Maslej et al. 2025; Bommasani et al. 2023) have also structured their reports in similar ways. By describing AI-related power disparities at three different granularities, we aim to provide both a high-level, simplified view of the most salient trends, and a low-level, detailed view of the trends in AI-related power disparities.

Measurement and reporting. We envision that the AI-PDI will be regularly measured and updated by an interdisciplinary group of experts, covering all AI actors, drawn from academia, industry, government, and civil society representatives. Ideally, this collaborative effort would operate under an established initiative such as the AI Index (Maslej et al. 2025), which already has a strong reputation for delivering comprehensive, trusted data on AI trends. By pooling diverse expertise and resources, the group can produce reports on the index with rigorous methodology, full transparency, and regular updates, so that the tool remains robust and relevant as the AI landscape evolves.

Interpreting the AI-PDI. It is important to note that the AI-PDI is not designed to advocate for an ideal or equal balance of power. We believe that there are certain differences between the kinds of power that different actors hold that are natural and desirable. For instance, governments should arguably have more power in passing regulations than technology companies. The goal is not to reduce the AI-PDI to zero; rather, the index is designed to track how power dynamics shift over time and help stakeholders determine the appropriate interventions to prevent worsening disparities.

Theory of change. The index aims to distill and simplify the complex concept of AI power disparity so that it can be understood and used by a broad audience, including policymakers, industry stakeholders, academic researchers, and civil society, to encourage the democratic value of power sharing in AI governance. We outline several potential use cases for different stakeholders.

Policymakers can benefit from the index’s evidence-based insights when formulating regulations or interventions aimed at addressing power disparities in the AI ecosystem. They can enact policies that prevent and mitigate problematic concentrations of power, aid actors or groups who might be marginalized, or develop mechanisms that hold powerful actors accountable. An example of a policy that has been put in place in response to growing power disparities is the E.U. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (2016). The GDPR aims to correct undesirable power disparities related to personal data processing by giving members of civil society more control over how their data, a key base in this power relation, is used. Similar policies could be enacted in the future if the AI-PDI shows that specific forms of power disparities between technology companies and other AI actors are increasing. In this sense, we envision the AI-PDI being used in a manner similar to how the HHI, a measure of market concentration, is used in U.S. Antitrust Law to assess the potential for monopolistic behavior and market dominance (U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission 2010). Industry stakeholders can use the AI-PDI as an accountability mechanism, encouraging efforts to reduce rather than exacerbate disparities. Here, we envision an impact similar to how the Foundation Model Transparency Index encouraged developers to become more transparent, on average, about their model building practices (Bommasani et al. 2024a). Academic researchers can use the index to investigate the trends in AI-related power disparities and conduct further research on the observed trends, proposing effective interventions and raising awareness. Members of civil society can use the AI-PDI to better understand and challenge existing power structures. The index can promote an informed dialogue among stakeholders by making the index publicly accessible and engender greater accountability and transparency in the development, deployment, and use of AI technologies.

Limitations. The AI-PDI has two main limitations. First, quantifying AI-related power disparities by definition simplifies the complexities of these dynamics in the AI ecosystem. Although it is inevitable that a quantitative metric will miss out on certain nuances that exist in the AI ecosystem, we believe that such a metric can still capture the most salient trends in an easily digestible manner and therefore be useful to a wide range of stakeholders.

Second, the indicators used to measure each dimension of AI power are inherently imperfect. While we outline a method for choosing these indicators based on established theories and expert input, they can only approximate the phenomena they represent. For instance, indicators such as the count of press releases for an actor’s means of influencing the political agenda do not fully capture the actor’s ability to determine what topics and issues are emphasized in media messaging. However, we believe that such proxies are still useful in understanding intangible concepts.

7. Conclusion

In this paper, we propose the AI-PDI, designed to highlight the macro-level power disparities driven by AI and to encourage policymakers, researchers, and the public to consider the broader societal impacts of AI beyond isolated technical metrics of performance, performance disparity, or adoption.

Our main contribution is a conceptual framework, building on existing work from philosophy and the social sciences, for operationalizing the high-level, complex, and multi-dimensional concept of power dynamics in the AI ecosystem. Through our conceptual framework, we break down power into various dimensions, including its bases, means, scope, and degree, to provide a detailed analysis of AI power and a holistic view of how this power has shifted in recent years.

For concreteness, we identify several key AI actor groups in the AI ecosystem and characterize what we believe to be the current major power trends in the AI landscape. However, we emphasize that our initial characterization is not meant to be comprehensive, and operationalizing the index will require substantial additional effort. In particular, we recommend operationalizing the index through the Delphi method, a structured, collaborative, and iterative process for gathering group input on broad topics. Using this method, a diverse pool of participants consisting of experts from academia, the technology sector, government, and civil society can provide input on all facets of the index. Similar to how the HDI shifted the global discourse on human development from monetary wealth to health, education, and standards of living, we hope that the AI-PDI will shift the global discourse on AI from technical performance and efficiency to power sharing and accountability.

Acknowledgements

This work was in part supported by the CMU-NIST Cooperative Research Center on AI Measurement Science & Engineering (AIMSEC), and the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the funding agencies.

Authors acknowledge valuable feedback from the participants of the “AI & Democratic Freedoms” events hosted by the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University. We thank M. H. Tessler, Kimberly Truong, and Andrew Somerville for the input they provided at various stages of this project.

This manuscript will appear in the proceedings of the 8th AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (AIES) in October 2025.

References

Ahmed, N.; and Wahed, M. 2020. The De-Democratization of AI: Deep Learning and the Compute Divide in Artificial Intelligence Research. arXiv:2010.15581.

Allen, D. 2023. Justice by Means of Democracy. In Justice by Means of Democracy. University of Chicago Press.

Aucoin, P.; and Heintzman, R. 2000. The Dialectics of Accountability for Performance in Public Management Reform. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 66(1): 45– 55.

Babbie, E. R. 2020. The Practice of Social Research. Cengage Au.

Bachrach, P.; and Baratz, M. S. 1962. Two Faces of Power. The American Political Science Review, 56(4): 947–952.

Baldwin, D. A. 2016. Power and International Relations: A Conceptual Approach. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691170381.

Beer, D. 2019. The Social Power of Algorithms. In The Social Power of Algorithms, 1–13. Routledge.

Benkler, Y. 2019. Don’t Let industry Write the Rules for AI. Nature, 569(7754): 161–162.

Berger, B. K. 2005. Power Over, Power With, and Power To Relations: Critical Reflections on Public Relations, the Dominant Coalition, and Activism. Journal of Public Relations Research, 17(1): 5–28.

Bommasani, R.; Hudson, D. A.; Adeli, E.; Altman, R.; Arora, S.; von Arx, S.; Bernstein, M. S.; Bohg, J.; Bosselut, A.; Brunskill, E.; et al. 2021. On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.07258.

Bommasani, R.; Klyman, K.; Kapoor, S.; Longpre, S.; Xiong, B.; Maslej, N.; and Liang, P. 2024a. The 2024 Foundation Model Transparency Index. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.12929.

Bommasani, R.; Klyman, K.; Longpre, S.; Kapoor, S.; Maslej, N.; Xiong, B.; Zhang, D.; and Liang, P. 2023. The Foundation Model Transparency Index. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.12941.

Bommasani, R.; Soylu, D.; Liao, T. I.; Creel, K. A.; and Liang, P. 2024b. Ecosystem Graphs: Documenting the Foundation Model Supply Chain. In Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, volume 7, 196–209.

Bovens, M. 2010. Two Concepts of Accountability: Accountability as a Virtue and as a Mechanism. West European Politics, 33(5): 946–967.

Brennan, K.; Kak, A.; and West, S. M. 2025. Artificial Power: AI Now 2025 Landscape. Technical report, AI Now Institute. Accessed: 2025-08-05.

Capraro, V.; Lentsch, A.; Acemoglu, D.; Akgun, S.; Akhmedova, A.; Bilancini, E.; Bonnefon, J.-F.; Branas-Garza, P.;˜ Butera, L.; Douglas, K. M.; et al. 2024. The Impact of Generative Artificial Intelligence on Socioeconomic Inequalities and Policy Making. PNAS nexus, 3(6).

Chouldechova, A.; Atalla, C.; Barocas, S.; Cooper, A. F.; Corvi, E.; Dow, P. A.; Garcia-Gathright, J.; Pangakis, N.; Reed, S.; Sheng, E.; et al. 2024. A Shared Standard for Valid Measurement of Generative AI Systems’ Capabilities, Risks, and Impacts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.01934.

Cisco. 2025. Cisco AI Readiness Index.

Colon Vargas, N. 2024. Exploiting the Margin: How Capitalism Fuels AI at the Expense of Minoritized Groups. AI and Ethics, 1–6.

Dahl, R. A. 1957. The Concept of Power. Behavioral Science, 2(3): 201–215.

Dahl, R. A.; and Stinebrickner, B. 2003. Modern Political Analysis. Prentice Hall.

Dastin, J. 2018. Insight - Amazon Scraps Secret AI Recruiting Tool that Showed Bias Against Women.

Diakopoulos, N. 2015. Algorithmic Accountability: Journalistic Investigation of Computational Power Structures. Digital Journalism, 3(3): 398–415.

Dor, L. M. B.; and Coglianese, C. 2021. Procurement as AI Governance. IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society, 2(4): 192–199.

European Parliament; and Council of the European Union. 2016. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council.

Feldstein, S. 2024. Evaluating Europe’s Push to Enact AI Regulations: How Will this Influence Global Norms? Democratization, 31(5): 1049–1066.

Grisham, T. 2009. The Delphi Technique: A Method for Testing Complex and Multifaceted Topics. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 2(1): 112–130.

Guzzini, S. 2017. Max Weber’s Power, 97–118. Cambridge University Press.

Handa, K.; Tamkin, A.; McCain, M.; Huang, S.; Durmus, E.; Heck, S.; Mueller, J.; Hong, J.; Richie, S.; Belonax, T.; and et al. 2025. The Anthropic Economic Index.

Harsanyi, J. C. 1962. Measurement of Social Power, Opportunity Costs, and the Theory of Two-Person Bargaining Games. Behavioral Science, 7(1): 67–80.

Haugaard, M. 2010. Power: A ‘Family Resemblance’ Concept. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 13(4): 419–438.

Heaven, W. D. 2023. Predictive Policing Algorithms are Racist. They Need to Be Dismantled. MIT Technology Review.

Hofstede, G. 1984. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values, volume 5. SAGE.

Janis, I. L. 2008. Groupthink. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 36(1): 36.

Joint Research Centre. 2008. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide. OECD publishing.

Kasy, M.; and Abebe, R. 2021. Fairness, Equality, and Power in Algorithmic Decision-Making. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 576–586.

Katell, M.; Young, M.; Dailey, D.; Herman, B.; Guetler, V.; Tam, A.; Bintz, C.; Raz, D.; and Krafft, P. M. 2020. Toward Situated Interventions for Algorithmic Equity: Lessons from the Field. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, FAT* ’20, 45–55. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9781450369367.

Kelly, J. 2024. (2024, October 28). How AI Could Be Detrimental To Low-Wage Workers. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackkelly/2024/10/28/how-ai-could-be-detrimental-to-low-wage-workers/.

Khodyakov, D. 2023. Generating Evidence Using the Delphi Method. https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2023/10/ generating-evidence-using-the-delphi-method.html. Originally published by Integration and Implementation Insights.

Kroll, J. A.; Huey, J.; Barocas, S.; Felten, E. W.; Reidenberg, J. R.; Robinson, D. G.; and Yu, H. 2017. Accountable Algorithms. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 165: 633–705.

Latzer, M.; and Festic, N. 2019. A Guideline for Understanding and Measuring Algorithmic Governance in Everyday Life. Internet Policy Review, 8(2).

Lazar, S. 2024. Automatic Authorities: Power and AI. arXiv:2404.05990.

Lazar, S. 2025. Governing the Algorithmic City. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 53: 102–168.

Linstone, H. A.; Turoff, M.; et al. 1975. The Delphi Method, volume 1975. Addison-Wesley Reading, MA.

Lowy Institute. 2019. Asia Power Index 2019: Key Findings. [Accessed: 2025-05-08].

Lukes, S. 2012. Power: A radical view [2005]. Contemporary Sociological Theory, 266(3): 1–22.

Maslej, N.; Fattorini, L.; Perrault, R.; Gil, Y.; Parli, V.; Kariuki, N.; Capstick, E.; Reuel, A.; Brynjolfsson, E.; Etchemendy, J.; Ligett, K.; Lyons, T.; Manyika, J.; Niebles, J. C.; Shoham, Y.; Wald, R.; Walsh, T.; Hamrah, A.; Santarlasci, L.; Lotufo, J. B.; Rome, A.; Shi, A.; and Oak, S. 2025. The AI Index 2025 Annual Report. Technical report, AI Index Steering Committee, Institute for Human-Centered AI, Stanford University, Stanford, CA.

McKeown, M. 2024. Straddling the Water’s Edge: How U.S. Big Tech Companies Aim to Shape U.S. Policy in the Intermestic Sphere.

Metcalf, J.; Moss, E.; Watkins, E. A.; Singh, R.; and Elish, M. C. 2021. Algorithmic Impact Assessments and Accountability: The Co-Construction of Impacts. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 735–746.

Metcalf, J.; Singh, R.; Moss, E.; Tafesse, E.; and Watkins, E. A. 2023. Taking algorithms to courts: A relational approach to algorithmic accountability. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 1450–1462.

Mukherjee, N.; Zabala, A.; Huge, J.; Nyumba, T. O.; Adem Esmail, B.; and Sutherland, W. J. 2018. Comparison of Techniques for Eliciting Views and Judgements in Decision-Making. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(1): 54–63.

Nissenbaum, H. 1996. Accountability in a Computerized Society. Science and Engineering Ethics, 2: 25–42.

Nye, J. S. 2004. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. Public Affairs.

Okoli, C.; and Pawlowski, S. D. 2004. The Delphi Method as a Research Tool: An Example, Design Considerations and Applications. Information & Management, 42(1): 15–29.

Oxford Insights. 2025. 2024 Government AI Readiness Index.

Payne, K. 2024. AI chatbot Pushed Teen to Kill Himself, Lawsuit Alleges. AP News. Accessed: 2025-05-21.

Portland Communications. 2019. The Soft Power 30. [Accessed: 2025-05-08].

Richardson, R.; Schultz, J. M.; and Southerland, V. M. 2019. Litigating Algorithms 2019 US Report: New Challenges to Government Use of Algorithmic Decision Systems. Technical report, AI Now Institute.

Rowe, G.; and Wright, G. 1999. The Delphi Technique as a Forecasting Tool: Issues and Analysis. International Journal of Forecasting, 15(4): 353–375.

Sagar, A. D.; and Najam, A. 1998. The Human Development Index: A Critical Review. Ecological Economics, 25(3): 249– 264.

Sattarov, F. 2019. Power and Technology: A Philosophical and Ethical Analysis. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield International.

Scheiber, N. 2016. Universities’ AI Talent Poached by Tech Giants. The Wall Street Journal. Accessed: 2025-05-21.

Schellekens, P.; and Skilling, D. 2024. Three Reasons Why AI May Widen Global Inequality.

Schiff, D.; Borenstein, J.; Biddle, J.; and Laas, K. 2021. AI Ethics in the Public, Private, and NGO Sectors: A Review of a Global Document Collection. IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society, 2(1): 31–42.

Selbst, A. D. 2021. An Institutional View of Algorithmic Impact Assessments. Harv. JL & Tech., 35: 117.

Singla, A.; Sukharevsky, A.; Yee, L.; and Chui, M. 2024. The State of AI in Early 2024: Gen AI Adoption Spikes and Starts to Generate Value.

Stinebrickner, B. (2015). Robert A. Dahl and the Essentials of Modern Political Analysis: Politics, Influence, Power, and Polyarchy. Journal of Political Power, 8(2), 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2015.1054579.

Suntsova, O. 2024. The Impact of “First-Mover Advantage” on Global Market Structure and Dynamics. Available at SSRN 5125609.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2025. Human Development Report 2025. UNDP (United Nations Development Programme).

UNESCO. 2023. Readiness Assessment Methodology.

U.S. Department of Justice, A. D. 2024. Herfindahl Hirschman Index.

U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission. 2010. Horizontal Merger Guidelines.

Varieties of Democracy Project. 2024. V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy). https://www.v-dem.net/. Accessed: 2025-0603.

Varoufakis, Y. 2024. Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism. Melville House.

Von Der Gracht, H. A. 2012. Consensus Measurement in Delphi Studies: Review and Implications for Future Quality Assurance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 79(8): 1525–1536.

Waelen, R. 2022. Why AI Ethics is a Critical Theory. Philosophy & Technology, 35(1): 9.

Waelen, R. A. 2024. The Ethics of Computer Vision: An Overview in Terms of Power. AI and Ethics, 4(2): 353–362.

Weber, M. 1925. Economy and Society: A New Translation. Harvard University Press.

Wieringa, M. 2020. What to Account for When Accounting for Algorithms: A Systematic Literature Review on Algorithmic Accountability. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 1–18.

© 2025, Rachel M. Kim, Blaine Kuehnert, Seth Lazar, Ranjit Singh, and Hoda Heidari

Cite as: Rachel M. Kim, Blaine Kuehnert, Seth Lazar, Ranjit Singh, and Hoda Heidari, The AI Power Disparity Index: Toward a Compound Measure of AI Actors’ Power to Shape the AI Ecosystem, 25-20 Knight First Amend. Inst. (Sept. 8, 2025), https://knightcolumbia.org/content/the-ai-power-disparity-index-toward-a-compound-measure-of-ai-actors-power-to-shape-the-ai-ecosystem [https://perma.cc/8PXY-QAS4].

By operationalization, we mean using a systematic method to gather additional input on the AI-PDI, allowing the index to move from the conceptual framework presented here to a set of concrete tools, consisting of indicators and measures reported in a format that is accessible to the public.

Rachel M. Kim is a PhD student in Societal Computing at Carnegie Mellon University.

Blaine Kuehnert is a PhD student in Societal Computing at Carnegie Mellon University.

Seth Lazar is a professor of philosophy at the Australian National University, an Australian Research Council Future Fellow, and a Distinguished Research Fellow of the University of Oxford Institute for Ethics in AI.

Ranjit Singh is the director of the AI on the Ground program at the Data & Society Research Institute.

Hoda Heidari is the K&L Gates Career Development Assistant Professor in Ethics and Computational Technologies at Carnegie Mellon University with joint appointments in the machine learning department and the Institute for Software, Systems, and Society.